Laughing Stock

- Myrrhman

- Ascension Day

- After the Flood

- Taphead

- New Grass

- Runeii

Melody Maker: September 7th 1991

With his back catalogue rereleased to haunt him and an album of remixes cutting him to the quick, Mark Hollis explains to Steve Sutherland why he must take legal measures to protect the reputation of 'Laughing Stock', his latest exploratory album.

"You say it's weird. I don't think it's weird. I think it's disgraceful!"

Mark Hollis is agitated, almost animated. This is extraordinary behaviour for a man about whom I used the word "reluctant" six times in one paragraph the last time I wrote about him. What can have happened to draw such anger from lips that characteristically tremble to form the curtest "maybe"? What outrage can have been perpetrated for him to have broken cover from his precious privacy in order to express his displeasure with such conviction?

Well, first there was "Natural History", a compilation album of Talk Talk tracks released by EMI after the band's contract with that label was terminated and they'd been released to ply their art elsewhere. EMI had been shocked by "Spirit of Eden", the innovative, improvisational and wilfully uncommercial album Hollis delivered to them in 1988. It was anything but the anticipated follow-up to "The Colour of Spring", the album of soulful hits that seemed to have guaranteed Talk Talk a future of filling stadia around the world. It was nearer the free jazz ethic of vintage Miles Davis than the soaring inanities of Simple Minds, and EMI waved Hollis farewell, presumably releasing "Natural History" as a way of recouping part of the small fortune they'd invested in "Eden".

"A compilation album is not my idea of an album," says Hollis today. "I don't like compilation albums and I didn't like that one. It certainly wasn't the selection of tracks I would have liked even if there had to be one. But, at the end of the day, they had every right to do it so…"

He shrugs his way into silence.

What really disgusts him is "History Revisited", the album of Talk Talk remixed by the like of Julian Mendelsohn and Gary Miller that EMI released after the company had lucked into discovering that, if they wacked a dancebeat under some of the band's finest early moments, the public could be duped into thinking they were buying something new and tres chic. To Hollis, a man for whom integrity is the very root and sole reason for making music, this was tantamount to artistic rape. He felt defiled, frustrated, furious and unclean — the way you feel if you've ever been unfortunate enough to return home to find you've not only been burgled and your most intimate possessions abused, but that the burglars have wantonly smeared shit on the walls.

"We're gonna take them to court over this remix thing," Hollis says and, believe me, he's near to tears. "To me, it's unbelievable they could do that. To have people overdubbing stuff you've done and putting it out…" The sentence evaporates in exasperation. It's the complete antithesis of the Talk Talk ethos. Everything he's worked for is being murdered, mocked for greed.

"I've never heard any of this stuff and I don't want to hear it…but to have people putting this stuff out under your name which is not you, y'know, I want no part of it. It's always been very important to me that I've got on with the people we've worked with. People's attitude has always been really important to me. So much of why someone would exist on one of our albums is what they are like as a person. So to find you've got people you've never give the time of day to going out as thought it's you…it's disgusting."

Hollis says he got wind of "History Revisited" before it was released back in March and sent legal letters to get it stopped. The letters were ignored so now Hollis, a man who it seems to me would do just about anything to avoid a confrontation, is taking EMI to court. This isn't business. This is strictly personal. Of course, the harm's been done — the record's out and it sold enough to take it high into the album charts. He was even nominated for a Brits Award on the back of the rereleases — a situation he finds as distressing as I find it ludicrous.

They showed film of us from 1984," he says, visibly shaking. "It was just insulting, wasn't it? I wasn't happy with it."

There are people who, ignorant of Talk Talk's evolution from Duranalikes to free spirits, will be expecting their new album, "Laughing Stock", to be some bubbly dancepop magnum opus. These people are going to be disappointed and Hollis says that's down to EMI. And so it is he's prepared to appear in court, to fight for the principle of the thing in the hope that a legal precedent might be set and others may not be forced to suffer the indignity he feels has been forced upon him.

When I arrive to interview Hollis, he is asleep on the sofa in a record company office incongruously crowded with taxidermy. He is uncomfortable talking about his music and — yes — reluctant to reveal much about himself. For this reason he's happiest doing his duty in offices like this where nothing of his personality is betrayed by his surroundings. His first suggestion was that we meet at my place — an idea which, it seems to me, suggests a positively obsessive desire to negate any possibility whatsoever of giving away unnecessary clues. That plan didn't come about because Hollis, who lives in the Suffolk countryside and visits London as seldom as possible, managed to organise a couple of meetings and the Maker interview all on the same day, thus minimising his journeys.

It's not that he's impolite or even that he begrudges intrusion. It's just that he's chronically ill at ease with the investigative process.

"I do this to be reasonable," he explains. "But I don't see that doing an interview does anything but detract from the album. I mean, the album was a year of me being as succinct as I can possibly be and me talking about it can only detract from that."

Hollis fears that words overembroider his work and that the more we say, the further we stray from the new album's purity of intention.

"The last thing I would ever want to do is intellectualise music because that's never been what it's about for me," he says. "Nothing has changed from the ethic of the last album and I would never want that to change because I can't see any way of improving upon that process. As before, silence is the most important thing you have, one note is better than two, spirit is everything, and technique, although it has a degree of importance, is always secondary.

So "Laughing Stock" is…

"…What it is," says Hollis.

It's not a reaction to anything, it's not a political statement with either a big or a small P. It has no axe to grind and no ulterior motive. "Laughing Stock" is just the rich recorded rewards of an organic process of working which Hollis adores.

What he does is collects a group of like-minded musicians together in Wessex Studios in North London where he can record the "perspective of instruments in physical distance rather than off the board", and then each player (there are 18 on "Laughing Stock") gets to improvise around a basic theme as he or she feels it. Imperatively, this process is continued over a long period of time ("Laughing Stock" took a year) until Hollis feels each player has expressed their character and refined their contribution to the purest, most truthful essence. Only then is the record complete.

"It's never a thing with any of these albums of knowing what they're going to sound like. It's more like knowing the kind of feel you want. The one kind of starting point we had this time was just this thing of everyone working in their own little time zone. Really, it's just going back to one of a couple of things — either the jazz ethic or y'know, an album like 'Tago Mago' by Can, where the drummer locked-in and off he went and people reacted at certain points along the way. It's arranged spontaneity — that's exactly what it is."

"Laughing Stock" will be released on the Verve label, an offshoot of Polydor that specialises in the esoteric. Hollis is pleased because the Mothers of Invention used to be on Verve although several people at Polydor are purported to be gutted at what Hollis has given them. How will they sell it?

The first time I heard the record was at a dinner given for retailers by the record company at The New Serpentine Gallery. It was an embarrassingly desperate attempt over cocktails to convince store owners that they should stock a record which, the company was trying to infer, stood for quality over likely quantity of sales. Nobody knew where to look as Hollis' muted blues confessional purposely disintegrated into shivering feedback. A similar farce was, apparently, held in a Paris planetarium.

Hollis attended both playbacks and survived. He says the Paris one wasn't too bad because, when the lights went out, it was close to the perfect way to listen to his music — with your eyes closed, watching your own mind movies. He didn't stick around in London, though — he had no desire to see people's reactions. He says he's proud of the record and, seeing as it wasn't made for other people, their opinions don't bother him.

He also denies there is any problem with Polydor: "Not at all, because the whole structure of the deal we have with this record company is understanding how we work. I suppose because it's on Verve some people will think we've been stuck under 'Jazz' but what on earth does jazz mean? It's such a vague term, isn't it? Without any question there are certain areas of jazz that are extremely important to me. Ornette Coleman is an example. But jazz as a term is as widely used and abused as soul — it no longer means what it should mean.

"Jazz has almost been bastardised to such an extent that, if you've got a saxophone on a record, it's jazz, which is a terrifying idea. It's like, where would you ever place Can? To me 'Tago Mago' is an extremely important album that has elements of jazz in it, but I would never call it jazz.

"Basically, the deal is that I promise to give them the best album I can. I think they have options across four albums which, at the pace we work, is the next 12 years. What more can you say?"

"Laughing Stock" isn't going to be a massive seller; everyone knows that and Hollis doesn't care. It's nominally divided into six parts although it's really one long piece spanning an evolution of moods. It begins with the fragmented blues scratching of "Myrrhman" (like John Lee Hooker played violas!), grows into the drizzle-burst lightning flash of "Ascension Day" where the words are little more than awkward static, and on into "After the Flood", a piece reminiscent of Robert Wyatt's Seventies fusion group Matching Mole, where a guitar of balletic grace is suddenly the cry of a pig being slaughtered, a minute-long one note feedback solo of which Hollis is particularly proud.

"Taphead" is even heavier, the guitar suggesting a blues progression but failing to follow through as if Hollis' grief is too great to even pursue the time-honoured route to anguished release. Trumpets puncture the flesh of the piece like arrows and the tension is well nigh unbearable until is suddenly dissolves into the lighter "New Grass" which is like a Haiku of King Sunny Ade, the spiritual awakening expressed through a homage to McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones, the percussive axis around which John Coltrane once weaved magic.

Finally there's "Runeii", a masterpiece of simple precision. There's not one note that doesn't need to be there, not a sound that fills to flatter.

"For things to endure, they need to be in their most pure form," says Hollis. "I mean, it wears on you if you're hearing all this echo or something all the time. You just thin, 'Let me hear this thing for what it is'."

Hollis is phobic about passive listening — he hates the notion that we don't choose what we hear the way we choose what we read or what we eat. It bothers him that we have been lulled into treating music as mere entertainment, at most a diversion, at least mere background sound. He sees music as a means to spiritual enlightenment, something to enrich the soul.

"Ideally, that's the way it should be, that's for sure. At the end of the day, the greatest music, if you look to singing, must be gospel. It can't be anything other because it's just from the heart."

Although you can't make it out without a lyric sheet, "Laughing Stock" is a deeply religious work.

"It's just about virtue, really, just about character, that's all it is. I can't think of any other way of being able to sing a lyric and actually sing it and feel it unless I believe in what I'm singing about. That goes back to the gospel thing. I'm not saying all lyrics have to be about religion but, in a way, there must be that kind of thing in it.:

Well, what is there to sing about? God, sex and death — that's all.

"Yeah, well, I've certainly picked up on two of the three."

Mark Hollis hasn't a clue whether Talk Talk bear any relationship at all to rock music as we know and love it today. He's never heard Ride, never heard Chapterhouse, never heard any of the bands who swooned when "Spirit of Eden" came out, enraptured by its textures and envious of its freedom of format.

"I'm really not familiar with what is happening," he says. "I haven't heard any of them but it's not because I'm in any way dismissive of what is currently happening. It's just that I'm basically uninformed. That's all it is. I don't for a minute think that we're out on some limb and there's no one that has an understanding of what we're doing. I would hate to think that and I'm sure there are a lot of people around right now with whom we would have an empathy but it's just that I don't know who they are."

I tell Hollis that some of the bands I've spoken to cite Talk Talk as an inspiration which he thinks is great. Most of them, though, will never be as brave or suicidal enough to abandon the more accepted avenues and plunge themselves into glorious self-indulgence the way he has.

"The less you compromise, the less you're prepared to compromise," he laughs. "I look upon us as being extremely fortunate that we can work absolutely the way we wish. That must surely be the ideal for everyone.

"When I finished 'Spirit of Eden', there was a long period where I never thought I would make another record because I just didn't know where to go or anything. It's never anything I can predict. It's like, I say I'm in a four album deal but there's no way of knowing that I can ever do four albums. I do not know. The only thing that I can ever hope is that I would never make an album for the wrong reasons and just stay with that ethic. I can't see the point of making an album for the sake of it. There's nothing that I would get from it."

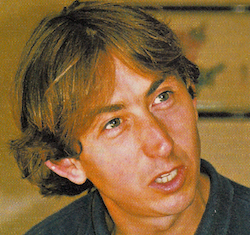

Mark Hollis shifts his bare feet off the table in front of him and informs [photographer Tom] Sheehan that, if he wants to take any photos, he'd better do it while we're talking because he just can't bring himself to pose.

Sheehan asks him to change seats with me so he's in the dying daylight and Hollis willingly complies.

"So there won't be a Talk Talk photo book coming out for Christmas?" says Sheehan, a mite sarcastically.

"I don't know," says Hollis, laughing nervously. "You'd better ask EMI. You never know, they might put one out with other people's heads grafted on our shoulders."

"Laughing Stock" is released on Verve on September 16. There will be no single taken from the album and no video.

^ go back to topMelody Maker: September 7th 1991

I may as well attempt to describe the dawn for you.

"Laughing Stock" begins with 18 seconds of amplifier hiss and it is instantly apparent that Talk Talk have achieved the improbable — made an album even more skeletal and abstract than "Spirit of Eden", even more organic, even closer to your inner ear. Each record they make now is an "Astral Weeks" — about its own atmosphere, an encapsulation, a world of its own.

How do they manage it? Apparently, "Spirit of Eden" took the best part of a year to create in the cavernous converted church of Wessex Studios. They turned the place into a kind of opium den, filled with candles and incense and liquid patterns projected onto the control-room walls. The sessions were slow and meticulous. Legend has it they once spend two days recording a string quartet and kept just one moment, a mistake the cellist had made. Another time brought in a large gospel choir, at considerable expense, captured some astonishing singing and then erased it all the following day. The spaces left by those decisions are important. You can hear them. Talk Talk records breathe. The detail is everything. Often, the tracks sound as if all the superstructure has been removed, like paint separated from its canvas, just a tissue of colour.

"Myrrhman", the opening song, is a prime example; a few flecks of viola and guitar held in place by the ambience of the room, delicate as a dragonfly wing. There are strokes of piano and double bass and Lee Harris — always an impressively sensitive and imaginative drummer — provides specks of brushed snare and cymbal. Above, no, amongst it lies Mark Hollis' unique and fragile voice. The sense is obscured, but his yearning tone is supremely articulate, seemingly aching for peace, redemption, and end to unknowingness.

Like Peter Green's extraordinary last works for Fleetwood Mac, Hollis appears to be reaching towards faith, seeking something to believe in. Somehow, "Ascension Day" manages to recreate the inner clamour of confusion, the turmoil of doubt, using a burning guitar sound, distorted organ and some splashy percussion. It erupts and ascends but, unable to resolve, stops dead at exactly six minutes. It's a startling moment.

Where previous albums have been CD clear and icy pure, "Laughing Stock" is bruised and grimy. Guitars buzz on the edge of screaming feedback, the strings flirt with discord, the brass is cracked and broken. "After the Flood" is tremendously brooding. In fact, there's a palpable sense of latent power throughout the album, as if, at any moment, Hollis will explode or expire from his frustration and sorrow. It's the tension that keeps it from being too solemn.

It's apt that Polydor have resurrected Verve — the label started in the 1950s by jazz impresario Norman Granz — for this release, as its explicit sense of mood places "Laughing Stock" closer to jazz than anything else, especially on "New Grass", the album's longest and most beautiful piece. Its mellow swing recalls the crepuscular fade to Van Morrison's "Madame George" or the translucent work of Bill Evans.

So, "Colour of Spring", "Spirit of Eden", and now "Laughing Stock". I make that three masterpieces in a row. It's tempting to wonder how they can possibly refine their vision any further. I hear the arguments about it being po-faced, a white, male, middle-class view of the world, but what the hell, why shouldn't it be? We should rejoice that somebody can still make records this adventurous. Talk Talk are certainly the most individual, possibly the most important group we have. Next to this glorious album most of what you have heard this year will seem inept and insignificant. Believe in it. (Jim Arundel)

^ go back to top

NME: 28th September 1991

Once upon a time Mark Hollis was the intense-eyed ranting lad who shouted "All you do is talk talk !". Then he became the anthemically melancholy lad who moaned "Its my life !" and never looked back from a life of anthemic melancholy.

As time goes by, Mark Hollis' music has slipped into a vat of dark, brooding melancholy so deep that even David Sylvian would join Right Said Fred rather than partake of its glummo brew.

In despair did EMI release an anthemically melancholy singles album and in more despair an anthemically melancholy dance remix album - an act on a par with releasing an Ambient House mix of Sham 69's "Hurry Up Harry", only not as interesting.

Now Hollis has gone to Verve and recorded "Laughing Stock" with 23 acoustically-oriented bass and organ and drum people. There is a slight jazz feel to this record. There are elements of soundtrack ambience. There are songs called "After The Flood". There are lyrics like "A hunger uncurbed by nature's calling". The whole thing is unutterably pretentious and looks over its shoulder hoping that someone will remark on its 'moody brilliance' or some such. It's horrible.

(4 out of 10) David Quantick

^ go back to topSelect: September 1991

Talk Talk have descended into complete introspection. The three of them seem to have been cooped up alone together since 1988’s intense Spirit of Eden, developing an otherworldly agoraphobia. There’s an addled melancholy to this album that caresses yet disconcerts, making for an uncomfortable listen.

If ‘Spirit’ glanced warily through the spy hole before opening the doors, Laughing Stock cowers at the other end of the corridor as you peer through the letter box. It requires your total concentration, a lights out night in.

Talk Talk despise the music business and all its machinations. The painfully entitled Laughing Stock is an exercise in self-indulgence and nothing more. If you refuse to enter their playground that’s fine by them. There is nothing remotely approaching a single within these six lengthy songs. Convention fastens the back seatbelt as Talk Talk’s organic songwriting process becomes ever more labyrinthine. The album is avant garde, an awkward mix of ambience, pop, jazz and blues.

And it doesn’t get any easier. It’s as if Talk Talk have set traps for you which only become apparent the more you listen to it. At face value, ‘After the Flood’ is a sultry, filmic epic but after a while it begins to yield an undercurrent of harsh interference. In both ‘Myhrrman’ and ‘Taphead’ there are sharp, unwarranted and unexpected bursts of noise – the latter’s literally startling. And ‘Ascension Day’ with its guitar building to a hornet’s nest of confusion then ending all at once, like a death in the family, is their angriest moment yet.

Talk Talk are being willfully reticent and difficult. Mark Hollis’s plaintive voice burns and quivers, distorting words to mere sounds, heightening the atmosphere. It’s as if they don’t want anyone to listen to the perverse genius of Laughing Stock. Well, screw them...

4/5

Nick Griffiths

^ go back to topThe Daily Telegraph: September 1991

When Talk Talk appeared a decade ago they were pasted with make-up and wrote twee, catchy synth-pop. They have mutated gradually. Now they are hermetic artists whose songs are barely songs at all, just long funeral-paced affairs in which instruments fade in and out of the mix. It’s a pleasant noise, but annoyingly passive, like waiting for a phone that never rings.

There are lyrics but Mark Hollis’s voice is so at sea amid the wash of sound that it’s hard to make out what he’s saying. One is torn between applauding all this as a sonic experiment and suggesting the band rename itself Mumble Mumble.

Chris Heath

^ go back to topThe Guardian: September 1991

Some listeners are moved to apoplexy by what they see as Talk Talk’s bottomless pretensions. They may have had a point with 1989’s Spirit of Eden, a baffling collection of unglued fragments. This time, though, the group have got their hooks firmly into a genuine new direction.

This violently uncommercial record operates in places rock and pop have mostly abandoned, though writer/vocalist Mark Hollis’s interest in Miles Davis’s collaborations with Gil Evans is a helpful clue. Largely cut loose from conventional melodies and chord-patterns, the music uses hazy, impressionistic layers of instrumentation to build moods of suppressed euphoria or probing melancholy. ‘Ascension Day’ is the most ‘rock’ thing here, though just as it builds up to a clashing crescendo of raw guitars, it’s abruptly cut off in favour of the peaceful, mystical surge of ‘After The Flood’. This eerie and meditative music demands a bit of effort, after which it can grow rapidly into obsession.

Adam Sweeting

^ go back to topThe Independent: September 1991

Talk Talk used to be a pop group of passable accomplishment, until they made enough money to scorn the wishes of their fans and make music the way they really wanted to; meandering, tune-free, chipped slowly out of improvisation rather than carved out of old-world limitations such as structure and songcraft. Real muso’s music, rock music that wishes it were jazz – than which there is nothing worse.

Laughing Stock, like its predecessor, Spirit of Eden, wants to be Astral Weeks, but had none of its dramatic conception and takes few of its chances. The results are No Fun in spades; crepuscular moods of cello and trumpet and heavily reverbed guitar, tippy-tap cymbals, double bass, funereally slow tempi [sic], blurry textures, whispered vocals, opaque lyrics and needlessly elongated tracks. This is the modern equivalent of ‘progressive’ music with all the snobby self-regard that implies.

The ‘songs’ here, of which there are apparently six, are at best half-glimpsed through the instrumental shrubbery which, despite Talk Talk’s obvious desire to make something fluid and organic, remains deathly throughout. As for Mark Hollis’s lyrics, heaven only knows what the poor chap is on about. Analysis, one suspects, may have proven cheaper.

Andy Gill

^ go back to topQ: September 1991

One year after million selling compilation Natural History and two years after the distinctly uncommercial Spirit of Eden, comes Talk Talk's new offering. That the group should choose to follow the experimental free-form moodiness of the latter rather than the seductively melodic compositions of the former will no doubt cause their new label a few heart-searching moments but, though Laughing Stock is even more withdrawn and personal then before, it does not disappoint.

Laughing Stock is clearly a descendant of Spirit of Eden. Like its predecessor, it contains just six lengthy tracks and continues Hollis's partnership with producer-contributor Tim Friese-Greene.

Musically too, Laughing Stock sounds as if it might have been culled from hours of improvisation, belonging to some spiritual whole. Two tracks share the same upbeat jazzy drum figure repeated throughout (the splashily percussive kind so often used as a rhythmic base for instrumental exploration), there are no gaps between tracks - indeed two overlaps - while two more share an opening guitar pattern.

There are no songs in the pop song-and-verse sense, rather an instrumental ebb and flow through a sparse musical soundscape. It's quiet but intense, using the familiar Talk Talk sounds of ringing guitar, acoustic double bass, near-motionless Debussy-like piano and swelling Hammond organ (supplemented on occasion by the equally subdued sounds of harmonium, clarinet, sax and mouth organ) drifting in and out of a loosely melodic structure with its own internal dynamics. Here too are the more abrasive sparks of free-form guitar and, more than once, the emotive mouth organ and simply bluesy guitar evoking the spirit of a doomed Robert Johnson facing the hellhound on his tail.

It is into this heavily suggestive atmospheric backdrop that Mark Hollis drops his periodic vocal appearances. Lyrically, he remains as elusive as ever. Some of his skeletal, cryptic lyrics are like a verbal equivalent of Twin Peaks where the images are precise enough but their meaning has to be divined. This time, however, there's a strongly mystical, almost religious theme running through titles like Ascension Day and After The Flood. The ideas of sin, dying and regeneration recur in almost every song, with images such as love and damnation, sacraments and blood casting a heavily fatalistic shadow over the glimpses of tunes, a mood of resignation reinforced by Hollis's mournful delivery or tremulous near whisper.

Jolly party music it isn't but Laughing Stock has its own brooding appeal which grows with every play. The melancholy mood, a rare thoughtfulness and the sense of sharing something deeply personal, together with the haunting, emotional quality of the understated music, put Talk Talk heavily at odds with the commercial charts where instant success is everything. Yet precisely the same qualities will ensure that even though Laughing Stock may lose Hollis some of his newly found friends, it will be valued long after such superficial quick thrills are forgotten.

**** (4 stars)

Ian Cranna

^ go back to topLes Inrockuptibles: Septembre/Octobre 1991

Quand Talk Talk débarqua, cheveux courts et oreilles longues, on étiqueta justement le groupe tête à claques pour rallye hyper young, copains de dortoirs de Spandau Duran. Puis un jour, Mark Hollis disjoncta et quitta en lévitation le carcan pop-song, gagnant par là même notre estime. Depuis, ses albums ne font plus danser les jeunes et s’étirent gracieusement en psychédélisme léthargique, le pouls ralenti jusqu’à l’extinction des feux. Musique ambiante, nuage chaleureux et envoûtant, dernière étape avant le silence. Ou comment le rock progressif entre dans ces pages par la grande porte. Interview JD Beavallet

Aujourd’hui, il ne reste qu’une seule chose importante sur mes disques, c’est silence. C’est même la chose qui compte le plus dans ma vie. On ne lui accorde plus assez de place. Sans arrêt, la télévision parle toute seule dans son coin, la radio est allumée sans raison. On ne devrait pas se laisser envahir de la sorte, il faut absolument sélectionner et choisir ce que l’on entend. C’est également vrai sur les disques. Je préfère encore entendre le silence qu’une note inutile, une note plutôt que deux. Ce que compte, c’est la façon dont elle est jouée. La technologie, la technique, tout ça ne sert qu’à remplir. Donc à rien.

La raison d’être mes albums est la spontanéité. Voilà pourquoi il me faut des années pour les enregistrer. La seule chose qui compte pour moi, c’est l ‘attitude des gens qui viennent jouer avec nous. Je veux qu’ils jouent pour eux-mêmes, je n’ai aucune envie de les diriger, de les orienter. Mon Travail consiste donc à sélectionner des musiciens dont j’aime l’attitude, je les invites et leur donne une liberté absolue.

Je les laisse tout seuls dans le studio et ils improvisent pendant des heures. Le lendemain, nous réécoutons ces heures de bandes et nous n’en conservons que quelques secondes...Ça prend donc du temps : parfois, certains musiciens doivent jouer seuls pendant dix heures avant que j’entende cinq secondes de musique dont j’ai besoin.

Pour un musicien, tu dois être impossible à vivre.

Je pense que c’est exactement le contraire, il est très facile de travailler avec moi. Chacun a une liberté complète, contribue au résultat final. Moi, je ne suis qu’un sélectionneur, je prends dans mon équipe les gens pour ce qu’ils sont et je leur demande juste de me donner ce qu’ils veulent. Je n’exige rien, je n’attends rien de précis, je les laisse faire.

Quand nous enregistrons, j’aime utiliser d’immenses studios. Ainsi, chaque instrument peut être déplacé pour que sa position lors due mixage soit juste. Ça me permet de ne jamais utiliser l’électronique : si je veux que l’instrument soit en retrait, je fais reculer le musicien par rapport aux autres. Car la plus grande partie de nos morceaux est enregistrée live. Nous arrivons en studio avec un cadre minimum, que nous jouons live. Ensuite, nous complétons avec des improvisations. Je ne sais donc jamais à l’avance à quoi ressembleront nos disques. Je sais juste ce que sera l’ambiance, mais c’est tout. He ne sais pas où les chansons iront. Je passe d’ailleurs plus de temps à effacer, à couper, qu’à enregistrer. Mon travail consiste surtout à épurer, encore et toujours…Des heures et des heures de bandes, dont il ne faut garder que quelques instants cruciaux. Nos musiciens ne comprennent pas que nous voulions garder ces petits bouts où ils se trompent, où ils se trouvent à côté de la plaque. Car ces erreurs m’intéressent, Moi, je n’ai jamais pu supporter la technique, ça ne m’a jamais impressionné. Voilà pourquoi le punk a tant compté pour moi. Chacun pouvait devenir un musicien, chacun était un musicien. Si tu ressens quelque chose, tu n’as qu’à le jouer. Même si tu ne sais jouer qu’une seule note, ça ne fait rien, tu es aussi important que n’importe quel autre musicien. Je resterai toujours fidèle à cet esprit punk.

A l’époque, le but était de faire le plus de bruit possible. Le tien semble être de faire le plus de silence possible.

Bien sûr (silence)...Mais à l’époque, je passais pourtant ma vie à acheter des disques, à écouter obsessionnellement de la musique. C’est grâce au punk que je me suis lancé à l’eau. J’étudiais la psychologie enfantine à l’université à ce moment-là, mais j’ai tout plaqué, le punk me paraissait autrement plus intéressant. Avant ça, la musique était trop technique, elle paraissait réservée à quelques-uns, je n’avais jamais envisagé de jouer. Je sais que ça paraît aujourd’hui difficile à concevoir, mais je faisais vraiment partie du mouvement. Pour moi, il n’y a pas de doute possible. En termes de musique, ce fut la période la plus importante de ma vie. Enfin, la musique appartenait à tout le monde, il existait plein de nouveaux endroits où jouer. Bien sûr, la majeure partie de ce que j’entendais était très éloignée de mes propres goûts, mais ça ne comptait finalement pas. L’important, c’était l’énergie et l’enthousiasme. C’était un peu comme les grands festivals en plein air : personne ne se soucie vraiment de qui va jouer, on vient pour être rassemblés, pour communiquer. Et moi, j’étais là, je jouais dan des groups, ça ne me serait jamais venu à l’idée auparavant, Les maisons de disques on été totalement dépassées par les événements, débordées par tous ces gens qui réclamaient de la musique. J’avais toujours pensé qu’elles ne comprenaient pas grand-chose à ce qui se passait mais, là la vérité. Eclatait au grand jour. Elles étaient déboussolées, n’avaient plus le moindre repère et signaient n’importe qui. Elles n’avaient aucun moyen de juger ce qui était bon ou mauvais, elles prenaient tout en bloc. C’était formidable.

Etais-tu, pour la première fois, autorisé à faire preuve d’originalité ?

L’originalité était tout pour moi. Je N’ai jamais eu envie de former un groupe tourné ver le passé, je ne vois pas où ça peut te mener.

Je parlais au niveau personnel.

Mais ce n’est pas moi qui compte. La seule chose importante, c’est de faire de la musique. En Angleterre, mes disques ne se vendent pas. C’est une situation idéale pour moi. Le reste de l‘Europe me fait vivre et pourtant, je conserve un anonymat total chez moi. J’ai le possibilité des faire les disques comme je l’entends, on m’en donne les moyens et je peux quand même être monsieur Tout-le-monde. Si j’étais reconnu dans la rue, je souffrirais de claustrophobie, comme si on m’enfermait. C’est un énorme danger que d’être trop concerné par soi-même et je suis ravi d’être anonyme. Moi, J’habite à la campagne, loin de tout. C’est très important pour mon état d’esprit. Mais dès qu’il faut enregistrer, je dois partir, revenir à la ville, à Londres. C’est extrêmement important de marquer une cassure. A la campagne, je ne me sentirais pas suffisamment à cran pour pouvoir enregistrer…J’ai quitté la ville il y a six ans, je voulais retrouver le sens de la communauté. Là où j’habite, je peux entrer dans les boutiques et parler aux gens. Ce n’est pas seulement l’argent que tu vas laisser sur le comptoir qui compte, cosmopolite de la grande ville me manque. J’ai besoin de revenir régulièrement à Londres, pour reprendre le contact.

Suicide Commercial

A vos débuts, Talk Talk était un groupe très différent : la musique était techno-pop, commerciale, l’image se rapprochait des néo-romantiques, vous étiez très propres, très polis vos disques se vendaient aux midinettes.

L’étape à laquelle nous sommes aujourd’hui parvenues n’est que la suite logique de nos débuts. Seules les contraintes ont changé. Pour notre premier album, nous n’avions eu que quatre semaines de studio, un budget très serré. Aujourd’hui, on nous laisse deux ans et nous pouvons dépenser autant d’argent que nous voulons. Voilà la plus grosse différence.

Ça n’explique pas la différence d’image.

Notre image était effrayante, je sais, mais ce n’était pas de notre faute. Nous nous étions longuement battus pour obtenir un contrat et sitôt après avoir signé, nous avons été assaillis par toutes sortes de pressions. Ça venait de tous les côtés, on a essayé de nous faire entrer dans un petite case avec laquelle nous n’avion rien à voir. Les directeurs artistiques des maisons de disques souffrent tour d’une même maladie : créativité, de leur propre personnalité, ile préfèrent essayer de les adapter au marché. Ils veulent une vague imitation de ce qui marche à l’époque, te poussent dans cette voie. C’est ce qu’ils ont essayé de faire avec nous au début. Les neo-romantiques étaient à la mode et nous avons subi d’énormes 0pressions. Elles ont durée jusqu’au début de l’enregistrement du second album.

Avais-tu honte d’accepter ces compromis ?

(Silence)…Je me suis retrouvé dans une position où je n’avais pas le choix. Mais je ne veux pas que tu croies que j’ai agi contre mon gré. Même si nous avons eu des problèmes à faire notre premier album, même si le producteur nous a été imposé, je ne peux pas renier ce disque. Même notre image ridicule a finalement eu des aspects positifs. C’est grâce à elle que j’ai compris que plus jamais je n’accepterai de jouer le jeu (sourire)…Si je n’avais pas accepté, je n’aurais jamais su qu’il fallait refuser et se battre.

Les pressions ont-elles également affecté votre musique ?

La seule erreur, c’est d’avoir accepté le producteur que la maison de disques voulait absolument nous imposer. Nous n’aurions jamais dû les laisser faire. Notre image nous a également longtemps porté préjudice. Quand nous avons signé avec EMI, notre image se rapprochait de celle des Doors, nous nous sentions en accord avec cette période du psychédélisme. Mais la maison de disques nous a nettoyés (sourire)…Ill fallait absolument briser l’image ridicule qu’ils avaient pensée pour nous. Je n’ai jamais été à l’aise dans le costume qu’ils nous taillaient j’avais l’impression de jouer dans une farce. Mais il fallait accepter certains compromis pour être plus fermes sur d’autres questions, comme notre refus d’apparaître sur les pochettes. Car pour moi, c’était ça le plus important de tout. Ma vraie image, c’est ma musique.

Les gens qui achetaient vos disques pour cette image proprette auraient-ils été surpris s’ils vous avaient rencontrés en privé ?

En privé, nous avons toujours été les mêmes, aujourd’hui comme hier. Les costumes blancs, les cravates, tout cela était absurde. Nous, nous portions des chemises psychédéliques, nous avions les cheveux très longs avant que la maison de disques nous envoie chez le coiffeur. Et très vite, nous sommes revenus à notre craie image, à ce que nous étions vraiment. He ne pouvais plus accepter de jouer le néo romantique pur faire plaisir à EMI. C’était à la mode, ces gens-là pensaient que c’était donc bon pour nous, que nous serions plus faciles à vendre ainsi…Ils ne savent pas ce que c’est de faire un disque, l’idée même de créativité n’a aucune valeur à leurs yeux. C’est pour cette raison que le punk a été si positif, car ils ont été renversés. Mais ils ont vite repris leurs esprits, nous sommes revenus à la case départ, avec les mêmes schémas, les mêmes petites cases, les mêmes moules. Regarde MTV : en 1981, je me souviens qu’ils voulaient renverser tout le monde, combattre le système des radios commerciales…Regarde-les aujourd’hui, encore plus formatés et obtus que ces radios.

On a ressort l’an passé toutes sortes de remixes house de vos anciens morceaux. C’était pour vous confirmer à ces formats ?

Je vais traîner EMI, notre ancienne maison de disques, devant les tribunaux. Il ont livré nos chansons à des DJ’s pour les remixer, ont sorti des compilations de dance-mixes de nos propres morceaux sans même nous en parler. Je refuse d’écouter ces disques.. C’est un scandale de donner ainsi mes chansons à des gens avec lesquels je ne travaillerais même pas dans mes pires cauchemars. Il on abâtardi mon travail, l’ont sorts à mon insu, ils devraient avoir honte. Mes chansons ne sont pas des cobayes, c’est répugnant de jouer ainsi avec. Quand je sors un disque, c’est que je le considère définitivement achevé. Je ne vois donc pas ce qu’il y a à enlever ou à rajouter, ce ne sont pas des cobayes.

Ta musique d’aujourd’hui est un secret bien gardé. Vous vous faites très rares dans la presse, comme si tu ne laissais les gens venir à tes disques qu’au compte-goutte.

Ça ne m’inquiète absolument pas que beaucoup de gens ne connaissent pas notre musique. D’ailleurs rien ne m’inquiète. J’aime que les gens viennent à nous petite à petit, qu’ils nous découvrent par le bouche à oreille. Nos disques ont une durée de vie très longue, ce qui est le plus beau compliment qu’on puisse leur faire. Les gens doivent y venir d’eux-mêmes, je ne veux pas les pousser. D’ailleurs, je ne pense pas que les interviews soient une bonne chose. Tout ce qui compte, ce sont mes disques. Moi, je ne peux pas être à leur hauteur, je ne peux pas être aussi succinct et clair qu’eux. Tout ce que je peux faire, c’est leu porter préjudice. Si j’avais le choix, je ne parlerais jamais à la presse. L’anonymat est une situation rêvée pour moi, celle qui me donner le plus d’espace. J’ai beaucoup de chance de ne plus écrire de tubes. Pour moi, le vrai succès est de pouvoir faire les albums dont j’ai envie. Je ne désire rien de plus.

Ta maison de disques, l’entend-elle de cette oreille ?

Chez EMI, nos disques ne faisaient pas l’unanimité. Il y avait mêmes des gens qui ne pouvaient pas nous supporter. Au moins, notre nouvelle maison de disques sait où nous en sommes, ils ont pu voir avec notre précédent album Spirit of Eden, dans quel état d’esprit nous nous trouvons. Je sais que nous sommes un groupe difficile pour eux, nous n’avons pas choisi la facilité et des gens nous en voudront forcément. Il est temps que ce milieu soit un peu plus créatif. Car je suis incapable de parler à des gens qui ne réfléchissent qu’en termes de produits, de formats, de calibres. Peu de gens aiment la musique dans les maisons de disques.

On a beaucoup parlé à propos de Talk Talk, de ‘suicide commercial’…

Bien sûr, notre réalité est un suicide commercial. Nos deux premiers albums ont été d’énormes succès mais je n’ai pas la moindre honte de ces disques. A cette époque, j’avais envie d’écrire des chansons, je voulais me limiter à ce format pop. Mais je n’ai jamais pris la décision nette d’arrêter d’écrire ainsi, de commettre un ‘suicide commercial’.

Nous avons juste évolué de façon naturelle. J’ai vieilli, j’ai été influencé par de nouvelles amitiés. Au début, c’était impossible d’établir une vraie relation avec un musicien. Nous les utilisions, tirions le meilleur d’eaux et les jetions s’ils nous convenaient plus. Mais au bout de dix ans, des amitiés sont nées, elles m’ont considérablement changé. C’est grâce à elles si nous n’avons jamais stagné. Au lieu de renouveler sans cesse nos musiciens nous préférons apprendre à mieux connaître notre cercle, à combattre ensemble la frustration…Car c’est elle qui nous pousse en avant, nous éloigne de tous ces formats limités. Même si nous ne savons pas toujours ce que nous voulons, nous savons ce que nous ne voulons surtout pas, nous pouvons donc le repousser ensemble.

Cette évolution entre un pop-music formatée et un musique sans réelle structure passe tout de même par une cassure, entre The Colour Of Spring et Spirit of Eden. D’où vient-elle ?

Apres The Colour of Spring, nous sommes partis en tournée. Ça a été la dernière de notre carrière. Jusque-là, la routine s’était installée depuis trois années : album, puis tournée…La grande différence vient de là : nous n’étions plus limités par le temps, nous n’avions plus la moindre échéance dans le futur. Nous avons donc pu commencer à travailler comme nous l’entendions, à improviser. Pour moi, les tournées étaient beaucoup trop rétrospectives. Dés qu’un morceau est enregistré, je n’ai plus la moindre envie d’y revenir. En plus, j’ai décidé d’avoir des enfants et ma famille passait au-dessus des concerts. De toute façon. Notre musique devenait de plus en plus difficile à reproduire sur scène. Les morceaux de notre nouvel album seraient d’ailleurs physiquement impossibles à jouer en concert.

Ces tournées t’ont-elles également conduit à des excès ?

Oui, il fallait que je sois ivre en permanence, c’était très inquiétant. Nous jouions six jours par semaine et je devais donc être totalement bourré six soirs par semaine. Ce n’était même pas un plaisir, mais une nécessité : sans alcool, j’étais incapable de monter sur scène. Quand nous avons commencé, c’est l’enthousiasme que me faisait grimper sur scène. Mais ça, je l’ai vitre perdu. La routine, la répétition l’avaient vite tué. Le seul moyen que j’avais d’apprécier notre musique, d’avoir l’impression d’y entendre un peu de fraicheur, c’était d’être défoncé en permanence.

C’est à ce moment-là que les drogues dont leur apparition ?

Ça, il faudrait que tu le demandes aux autres membres du groups. En ce qui me concerne, ce n’était que l’alcool. C’est la seule substance qui m’intéressait, j’en prenais plus que de raison. Je m’écroulais à la fin de chaque concert, ça ne pouvait plus durer ainsi. Je n’en pouvais plus de vivre dans une bulle, de traverser des pays sans même les voir. Ma vie devenait très malsaine.

Etes-vous totalement `å l’écart ou vous sentez-vous des affinités avec d’autres musiciens, comme It’s Immaterial ou Blue Nile ?

Je n’ai jamais entendu parler d’eux. Je ne connais personne qui écoute de la musique actuelle, si bien que je n’ai pas le moindre moyen de me tenir informé. Je refuse d’écouter la radio de regarde la télé, j’y entends trop de choses que je n’ai pas envie d’entendre. Par contre j’ai de bons guides dan d’autres domaines musicaux, des amis qui m’orientent ver des choses plus anciennes. J’ai totalement arrêté d’acheter des disques récents le jour où j’ai commence à en sortir moi-même et pourtant, j’écoute toujours autant de musique. En ce moment, j’ai trois passions : Ornette Coleman, Robert Johnson et la musique contemporaine, des gens comme Messiaen, Ligeti, Penderecki ou Stockhausen…Tous ces gens qui travaillent sue un musique sans forme réelle. De la pop-musique, je ne sais absolument rien, je suis incapable de te dire ce que se passe. Ma musique et aujourd’hui plus proche de jazz ou de Robert Johnson que de tout ça. Dans le jazz, j’aime que chacun des musiciens puisse jouer dans son propre espace.

Tu te concentres totalement dans ton rôle, sur ta propre voie et parfois, au cours du morceau, tu rejoins les autres et tu fais en leur compagnie un petit bout de chemin. C’est pour cette raison que je considère Tago Mago, de Can, comme un disque très important. Le batteur cogne dans son coin, ne ralentit jamais, n’accepte aucun compromis. Lui suit une ligne droite à vitesse constante et les autres vont et viennent autour de cet axe. Sans vouloir intellectualiser notre musique, j’aime que chacun puisse voyager à son rythme, seul ou parfois en groupe.

Est-ce une attitude calculée, réfléchie ou cette façon d’enregistrer est-elle naturelle ?

Ça peut être forcé, car ce n’est pas aisé de s’enfermer ainsi dans son coin. Mais en studio, tous les instruments sont branchés en permanence, il n’y a rien de prémédité, de calculé…Si l’un de nous a envie d’essayer une idée, il la met immédiatement en application. Parfois, c’est plus réfléchi : sur le premier morceau de l’album, par exemple, on a l’impression que le batteur installe ses fûts pendant que les autres ont déjà commencé à jouer, qu’il ne sera prêt que pour le second morceau. Ça, je l’ai voulu, c´était prévu. Idem pour le long solo du troisième morceau. Une seule note, bloquée pendant plusieurs minutes, j’en rêvais depuis des années (sourire)…

Es-tu agacé par les étiquettes ‘rock progressif’ ou ‘new-age’ accolées à votre musique?

Rien sans ce monde ne m’agace. Si des gens pensent que nous ressemblons à King Crimson, c’est qu’ils y voient des ressemblances. Moi, j’y vois plutôt le Velvet underground. Car il faut savoir que l’originalité n’existe pas. Toute musique naît forcement d’impressions ressenties à l’écoute d’autres musiques. L’originalité, au mieux, c’est la diversité, l’éclectisme. Le new-age, je ne sais pas ce que c’est, je ne connais que le nom. C’est une philosophie ? Très bien. Elle prône l’exploration de soi-même ? Ah oui, ça l’air formidable (rires)…

Et toutes ces références obscures à la religion ?

Mes paroles parlent avant tout de valeurs et d’attitudes. C’est une constante, les seuls sujets sur lesquels je peux chanter avec conviction. Le mot ‘soul music’ a pris un sens totalement différent, de ‘musique de l’âme’. Mais aujourd’hui, je me sens proche de ça, du gospel. C’est le cœur qui change. En ce sensé, oui, mes paroles sont religieuses. Mais pas d’une religion spécifique, seulement humanistes. Voilà où s’arrête ma religion. De toute façon, mes paroles sont écrites à propos d’un personnage qui n’est pas moi-même. C’est lui qui ressent les sentiments, qui les exprime. Et curieusement, quand je chante ces textes, quand je ferme les yeux, je ressens exactement les mêmes choses qui lui.

^ go back to topOor: 5 October 1991

Spirit of Eden stond zowel voor de opbouwende als de vernietigende krachten die het leven bepalen. Op Laughing Stock lijkt Mark Hollis de man achter en het enige overgebleven lid van Talk Talk, definitief gekozen te hebben voor een wereld van hoop. Door Corne Evers.

De werkelijkheid van de platenbusiness is vaak die van de jonge, enthousiaste muzikant die op een gegeven ogenblik aan het succes mag ruiken en uiteindelijk voor de verlokkingen van de commercie door de knieën gaat. Money for nothing, chicks for free heet het dan, veen bezwijken maar niet Mark Hollis. Na met zijn groep Talk Talk hits te hebben gescoord met nummers als It’s My Life, Such a Shame, Dum Dum Girl, Life’s What You Make It en Living in Another World, bouwde Hollis in 1988 op de langspeler Spirit of Eden breekbare emoties en melancholieke sfeerbeelden uit tot een concept waarbij de popmuziek bijna geheel het loodje legde.

Hartslag

Tegen de inktzwarte hemel glijden geruisloos de twaalf tekens van de dierenriem voorbij. Sterrenbeelden doemen op uit niet en verdwijnen weer. Het knipperlichten van verre planeten. Het planetarium in Paris is een wereld van rust. Buiten bestaat niet meer. Een gitaar laat zich voorzichtig horen, geluid kringelt als sigaretten rook omhoog, het zachte getinkel van een piano. “Place my chair at the backroom door” klinkt die bekende, klaaglijke stem. Help me up, I can’t wait anymore’. Myrrhman. Dan de rest. Laughing Stock. De muziek doet vreemd aan, een aaneenschakeling van sferen, sommige behoorlijk rauw, waarin jazz, klassiek en zelfs blues een rol spellen maar nauwelijks nog als zodanig herkenbaar zijn. Abstracte gitaarerupties wisselen af met emotionele zanglijnen, vaak is er sprake van een hypnotiserend soort broeierigheid. Songs in de traditionele zin van het woord, zijn er niet, er is geen refrein, geen koortje te bekennen, alleen die stem die zingt over kwetsbaarheid, over mededogen, over het geloof in een christendom zonder leugens, zonder hypocrisie. En er is een puls, een altijd voortdurende puls, als een hartslag, soms duidelijk, soms nauwelijks waarneembaar, maar hij is nooit helemaal weg.

Na afloop, als de laatste tonen zijn weggestorven en het licht weer aan, is het even stil. Er wordt beschaafd geklapt. Slechts een enkeling reageert ronduit enthousiast. “mijn God” zegt een Zweedse journaliste in een geaffecteerd soort Engels. Het afgrijzen in haar stem liegt er niet om. Je hoort haar denken: ‘Hoe ken iemand zoiets maken?’ Mark Hollis zit weggedoken op de achterste rij, duidelijk verlegen met de situatie. “ik ben blij dat je er bent”. Complimenten van mijn kant worden beantwoord met nerveuze excuses. “Sorry, misschien is dit wel niet de meest geschikte plaats om de plaat te horen.”

Anti-popheld

Een popster zal mark Hollis nooit worden. Zonder dat hij daar nou zelf bewust naar heeft gestreefd, is hij in de loop der jaren de verpersoonlijking van de antipopheld geworden, een muzikant met een gezin en zijn werk in de studio, die verder het liefst met rust wordt gelaten. Niet uit onvriendelijkheid, oh nee, Mark Hollis is de vriendelijkheid zelve, gewoon omdat hij naar eigen zeggen niets te melden heeft. Hij doet sowieso al maanden over een songtekst van een paar regels. “Het is zoveel moeilijker om iets in tien woorden te zeggen dan wanneer je duizend woorden tot je beschikking hebt. In mijn teksten zit mijn leven. Ze zeggen veel meer over mij dan welk interview dan ook. Ze zijn het resultaat van mijn observaties en representeren de waarden ik geloof, op het humanitaire vlak.

In wat voor wereld leef jij, Mark” vroeg ik hem ten tijde van Spirit of Eden. We zaten in Artis. Op het tafeltje tussen ons was het een druk komen in gaan van mussen die zich luid kwetterend van ons ontbijt trachtten meester te maken en zich daarbij van geen mens iets aantrokken. Alsof ze voelden dat ze van hem niets te duchten hadden, een dromer die houdt van het leven, van alles wat kruipt, zwemt, loopt en vliegt, een dromer in zijn eigen wereld.

Dat is een behoorlijke moeilijke vraag, weet je?

Geef me die maanden drie maanden en dan stuur ik je een antwoord.

Drie drie maanden werden drie jaren maar eindelijk is Mark Hollis er dan in geslaagd om zijn antwoord re formuleren: Laughing Stock. De teksten zijn directer, eenvoudiger dan ooit. Ze ademen een diepe spiritualiteit, vertrouwen. Als ik mocht kiezen, dan zou er een God bestaan, absoluut. Ik geloof in een menselijke vorm van christendom, in religie, welke religie ook, die is gebaseerd op de vrijheid om zelf keuzes te maken, op respect voor elkaar.

:Later, aan boord van de boot die ons over de Seine door Parijs bij avond voert, eet hij zonder morren de glibberige omelet met vette frieten die een hufterige over hem voorzet, nadat Hollis hem er bij herhaling op attent had gemaakt vegetariër te zijn. We praten over muziek, over jazz, over klassiek, over zijn bewondering voor Coltrane en Gil Evans, over Ligeti en het wonder van de compositie waarin slechts een toon wordt gespeeld. “ik geloof in eenvoud”.

De Zweedse vraagt hem of hij er nooit aan gedacht heeft dat mensen wel ween met onbegrip op zijn muziek zouden kunnen reageren. Hollis haalt zijn schouders op: “Ik verwacht niets van niemand. Die enige van wie ik iets verwacht, ben ik zelf. Ik kan niet weken aan de hand van de verwachtingen die andere mensen hebben. Iedereen heft het recht datgene wat ik doe aantrekkelijk te vinden of het af te wijzen. Er zullen best wel mensen zijn die het absolute rotzooi vinden. Ik zou ook niet anders willen. Zolang als je met je werk dat kunt doen wat je graag wilt, zit je nooit op het verkeerde spoor. Mensen vonden Spirit of Eden van dapperheid getuigen. Maar zeg nou zelf, wat is er nou dapper aan om gewoon verder te gaan vanuit een natuurlijke ontwikkeling van de dingen? Spirit of eden was wat ik altijd had willen doen. Het is eigenlijk het tegenovergestelde van dapper. Ik ben een heel gelukkig mens dat ik de mogelijkheid heb om aan mijn eigen verlangens tegemoet te kunnen komen, zonder dat me allerlei beperkingen worden opgelegd.

Rust

Als muziek ‘sferisch’ wordt genoemd, bedoelt men vaak dat de gehoorde klankenreeksen ingetogen van karakter zijn, dat ze een meditatieve uitstraling hebben. Laughing Stock is anders. De plaat kent momenten van rust, als het Hammond orgel van producer Time Friese-Greene (het enige ‘vaste’ Talk Talk lid naast Hollis) even niet kreunt en jammert maar in plaats daarvan pastelkleurige melodielijnen trekt. Vaker echter is er sprake van een uitbundige vorm van expressie, als de instrumenten plus de stem van Hollis in wilde vegen over elkaar lijken te zijn gezet, zoals een schilder ver op het doek ken ‘smijten’ ogenschijnlijk onstuimig en aan een primitieve innerlijke dwang tegemoetkomend maar tegelijkertijd heel bedachtzaam, met elke kleur nauwgezet op de juiste plaats aangebracht. Mark Hollis zou zelf het woord ‘bedachtzaam’ niet willen gebruiken. “Ik zoek niet naar iets, in die zin dat ik echt niet al weet wak ik wil gaan doen, op het moment dat ik de studio in ga. Er zijn op dat moment bepaalde dingen belangrijk, dat wel. In die geval was dat bijvoorbeeld New Morning van Bob Dylan, uit 1971, geloof ik. Op een gegeven moment heb je dan de band in de ruimte voor je en dan ga je aan het werk, zonder trucs, gewoon: wat je hoort, is wat je krijgt. Ik hou daarvan, zeker met betrekking tot de vocalen op dit album. Ik wilde niets kwijtraken, door het toevoegen van allerlei echo apparatuur en dergelijke. Er komt een moment dat je daar een punt achter zet, alleen nog maar een soort basisgeluid wilt. Het enige echt belangrijke om een bepaald soort atmosfeer te creëren, zijn tijd en rust. Ik denk echt dat rust het belangrijkste element in muziek is. Ik vergelijk dat altijd met film, met het werk van den Franse regisseur Marcel Carne, die voor mij echt de absolute top is. De twee dingen in zijn films waar hij het meest mee werkt, zijn rust en karakter, De verhalende lijn komt voor hem pas later. Zo zou ik ook muziek willen maken, nooit iets spelen alleen maar om het spelen. Ik heb altijd geloofd dat een noot beter is dan twee en uiteindelijk gaat dat naar een punt dat niet beter is dan iets Stilte moet altijd hoger gewaardeerd worden dan wat anders ook. Bij een plaatopname moet de hoogste prioriteit uitgaan naar die momenten waar geen geluid nodig is.

Prikkels

Het rijtje invloeden dat Mark Hollis noemt, is al jaren overanderd: Miles David, Gil Evans, Ravel, Satie, Debussy en nog een paar. Gevraagd hoe hij met deze invloeden omgaat, hoe hij de prikkels die hij van de muziek van deze componisten krijgt, in de studio voor zijn eigen creatieve proces aanwendt, is een diepe zucht in eerste instantie het enige antwoord. “ik weet het niet. Het voorbeeld van New Morning, wat ik je gaf, dan zijn er elementen op zo’n plaat die ik graag in mijn eigen muziek zou horen. Wat de drummer Can van doet op Tago Mago, die deel afgemeten manier van drummen, dat spreekt me aan. Maar ook het feit dat daar vier mensen samenspeelden die allemaal verschillende ideeën hadden over wat nu de off-beat was en wat de on0beat, maar die ieder voor zich in hun hoofd precies wisten wat ze aan het doen waren en die elkaar op diverse punten langs de muzikale lijn ontmoetten. Miles Davis en Gil Evans, ik heb altijd enorm gehouden van het illustratieve aspect van hun muziek.

Hij zakt even weg, een afwezige blik in zijn ogen. ‘Techniek is voor mij nooit belangrijk geweest. De mensen met wie ik werk, hebben een hoop technische bagage tot hun beschikking, daar niet van, maar dat is nooit de reden geweest om met ze te werken. Het was altijd meer een kwestie van houding, het gevoel dat iemand in twee noten kan leggen. En als datgene wat ik te zeggen heb, met een noot kan, dan gebruik ik maar een noot. Dat is het volgende stadium. Het gaat dan niet over virtuositeit maar over attack.”

Waar dat moet eindigen, weet ook Mark Hollis niet. “Ik zou best heel minimaal willen werken. Ik denk dan bij sommige tracks hoe aardig het zou zijn om het allemaal heel simpel te maken. Het probleem is dat je echter altijd de dynamiek van het geheel in de gaten moet houden, omdat je dingen wil doen die heel breekbaar zijn en andere dingen die daar helemaal aan tegenovergesteld, enorm gewelddadig zijn. Dat is waar je rekening mee moet houden, wil je tenminste dat de plaat echt van de ene sfeer in de andere kan overgaan.”

Optreden doet hij nog steeds niet. “Ik wil niet. Op de eerste plaats is het onmogelijk om dit soort materiaal live te spelen, de verschillen in dynamiek zouden een te grote belasting voor de muzikanten vormen en ik zou minstens twintig mensen op het podium moeten hebben. Een ander en eigenlijk veel belangrijker punt is het gegeven dat ik anderhalf jaar aan de arrangementen van Laughing Stock heb gewerkt. Het laatste waar ik nu behoefte aan heb, is om het eerstvolgende jaar vrij te moeten houden om alles opnieuw te arrangeren. Dat zou de omgekeerde weg zijn voor mij. Laughing Stock is nu verleden tijd. Ik wil graag verder naar de toekomst.

^ go back to topOor: 5th October 1991

Spirit of Eden stood both for the constructive if the destructive forces that determine life. On Laughing Stock Mark Hollis, the man behind it and the only remaining member of Talk Talk, seems to have finally opted for a world of hope. By Corne Evers.

The reality of the record business is often that of the young, enthusiastic musician who at any given moment may smell success and ultimately be brought to their knees by the lure of commerce. “Money for nothing, chicks for free” it was called then, many succumb, but not Mark Hollis.

After scoring hits with his group Talk Talk with songs like "It's My Life, Such a Shame, Dum Dum Girl, Life's What You Make It and Living in Another World, in 1988 Hollis created the LP Spirit of Eden where fragile emotions and melancholic atmosphere were made into a concept where pop music is almost entirely unexplained.

Heartbeat

Against the ink black sky the twelve signs of the zodiac glide silently past. Constellations loom from nowhere and disappear again. The flashing lights of distant planets. The planetarium in Paris is a world of peace. The outside no longer exists. A guitar can be heard gently, sound like cigarette smoke curls up, the soft tinkling of a piano.. "Place my chair at the back room door" sounds that familiar, plaintive voice. “Help me up, I can't wait anymore '. Myrrhman. Then the rest. Laughing Stock. The music is strange, a concatenation of atmospheres, some pretty raw, in which jazz, classical and even blues play are role but are barely even recognizable as such. Abstract guitar eruptions alternate with emotional vocals, often there is a mesmerising kind of fog. Songs in the traditional sense of the word, there aren’t, there is no chorus, no choir in sight, only the voice that sings about vulnerability, about compassion, about faith in a Christianity without lies, without hypocrisy. And there is a pulse, a continuous pulse, a heart beat, sometimes clear, sometimes barely perceptible, but never completely gone.

Afterwards, when the last notes have died away and the lights back on, it is equally silent. Civilization has collapsed. Only a few respond with downright enthusiasm "My God," says a Swedish journalist in an affected sort of English. The horror in her voice does not lie. You can hear her thinking: "How did someone make something like this? 'Mark Hollis sits huddled in the back row, clearly embarrassed by the situation. "I'm glad you're here." My compliment are answered with nervous excuses. "Sorry, maybe this is not the most appropriate place to hear the album."

Pop Anti-hero

Mark Hollis will never be a pop star. He has now self consciously striven, over the years, to become the personification of the anti-pop hero, to become a musician with a family and his work in the studio, and further to preferably be left alone. Not out of hostility to, oh no, Mark Hollis is kindness itself, simply because he say he has nothing to say. He works for months on lyrics of a few lines. "It is so much harder to say somthing in ten words when you have a thousand words at your disposal. In my lyrics is my life. They say a lot more about me than any interview. They are the result of my observations and represent the values I believe, on the humanitarian level.

“In what sort of world do you live, Mark?", I asked him at the time of Spirit of Eden. We sat in Artis. On the table between there was pressure from loud twittering sparrows who tried to seize our breakfast and in so doing were attracted to something of the man. As if they felt they had nothing to fear from him, a dreamer who loves life, everything that crawls, swims, runs and flies, a dreamer in his own world.

That is quite a difficult question, you know? Give me some months, three months and I’ll send you a reply.

Three months, three years, but finally Mark Hollis managed to formulate his answer re: Laughing Stock. The lyrics are more direct, easier than ever. They breathe a deep spirituality, confidence. If I could choose, would God exist, absolutely. I believe in a human form of Christianity, in religion, any religion, which is based on the freedom to make choices for themselves, on respect for each other.

Later, aboard the boat that carries us over the Seine through Paris at night, he eats without complaint the slippery greasy omelet with fat French fries without murmur, after Hollis's repeated studies have made him vegetarian. We talk about music, about jazz, classical, his admiration for Coltrane and Gil Evans, Ligeti and the miracle of composition in which only one tone is played. "I believe in simplicity."

The Swedish journalist asks him whether he ever thought that people would react with incomprehension to his music. Hollis shrugs: "I expect nothing from anybody. There’s only one of whom I expected something, muself. I can’t soak in the light of other people’s expectations. Everyone has the right to find what I do attractive, or reject it. There will be people who find it an absolute mess. I also wouldn’t want. As long as you can do what you like with your work you’re never on the wrong track. People felt Spirit of Eden of was brave. But honestly, what’s brave in just moving on in a natural progression of things? Spirit of Eden was what I always wanted to do. It's actually the opposite of brave. I am a very happy man in that I have the opportunity to satisfy my own desires, withouth all kinds of restrictions being imposed.

Rest

If musical spheres are mentioned, it’s often meant that the sounds heard are of a subdued character, that they have a meditative aura. Laughing Stock is different.

The album has moments of calm, like the Hammond organ of producer Tim Friese-Greene (the only 'fixed' Talk Talk member alongside Hollis) not just moans and wails, but pastoral melody lines. More often, however, there’s an exuberant form of expression, as the instruments- plus the voice of Hollis – seems to have been put down in wild sweeps, like a painter flinging paint on the canvas through a seemingly impetuous and a primitive inner compulsion, yet at the same time very thoughtfully, with every colour in exactly the right place.

Mark Hollis would not use the word ‘mindful’. "I don’t search for something in the sense that I really didn’t already know what I wanted to do when I went into the studio. There are at that moment certain important things, though. In that case it was at New Morning by Bob Dylan, in 1971, I believe. At some point you have the band in the room with you and then you go to work, no tricks, just ‘what you hear is what you get’. I love it, especially regarding the vocals on this album. I wanted to lose nothing by adding all sorts of echo equipment and such. There comes a time when you do move beyond a certain point, but there is only a basic sound. The only really important thing needed to create a certain kind of atmosphere; is time and rest. I really think that peace is the key element in music. I always compare it with film, with the work of the French director Marcel Carne, which for me is really the absolute best. The two things in his movies he works with most, are quietness and character, where for hin the narrative line comes later. So I would also want to make music, never just play to play. I have always believed that one note is better than two and eventually gets to a point that one is not better than nothing. Silence should always be valued higher than anything else too. When recording a record the highest priority should be given to those times when no sound is needed.

Incentives

The list influences that Mark Hollis cites, has long been static: Miles Davis, Gil Evans, Ravel, Satie, Debussy and a few others. Asked how he deals with these influences, how he uses the stimuli that the music of these composers prodice, in the studio for his own creative process, a deep sigh is at first the only answer. "I don’t know. In the example of New Morning, which I gave you, there are elements you would hear in those albums that I like in my own music. What the drummer of Can isof doing on Tago Mago, which is a measured drumming, appeals to me. But also the fact that there are four people playing together who all have different ideas about what is now the off-beat, and what the on-beat, but each of them in their head know exactly what they were doing and met each other at various points along the musical line. Miles Davis and Gil Evans, I've always loved the enormous illustrative aspect of their music.

He just tails off, a distant look in his eyes. "Technique has never been important to me. The people with whom I work, have a lot of technical skills at their disposal, but that’s never been the reason for working with them. It was always more a matter of attitude, the feeling that someone can explain in two notes. And if what I have to say, I can say with a note, thenI use only one note. That is the next stage. This is not about virtuosity, but about approach. "

Where it should end up, Mark Hollis doesn’t know. "I would like to work, at best, very minimally. I think that with some tracks how nice it would be to make it all very simple. The problem is that you always need to watch the dynamics of the whole, because you want to do things that are very fragile and other things that are the complete opposite, very violent. That's where you need to consider, you'll want at least that the record can pass from one atmosphere to another.”

He still won’t tour. "I don’t want to. First, it is impossible to play this kind of material live, the differences in dynamics would be an excessive burden for the musicians and I would need at least twenty people on stage. Another, and actually much more important point, is the fact that I have worked for 18 months on the arrangements of Laughing Stock. The last thing I need to do is to have the next year off having to keep re-arranging everything. That would be going in the opposite direction for me. Laughing Stock is now history. I would like to continue into the future.

^ go back to topNME: October 12th 1991

They were born in age of synth-pop and teenybop gunslingers, but Talk Talk were always sullen and strange....and now they're 100 percent Obtuse Damn Bugger Weird. Simon Williams meets a serene, laid-back Mark Hollis, and discovers his favourite word is 'organic'.

The story of Talk Talk is a strange and twisted affair. Once upon a time, their peers were Duran Duran, Cava Cava, Wank Wank and all those double- barrelled teenybop gunslingers with scary big suits and a terrifying taste for (barfo barfo) synth-pop.

This just happened to be something Talk Talk were extremely good at, although, with Mark Hollis' pinched, nervy face poking at the camera, the Talkies managed to avoid tumbling into the sun-bronzed Smash Hits glamdom.

While their contemporaries made naff vids in exotic locations (Duran), bought Porsches (Spandau), grew crap haircuts (Kajagoogoo), or turned into gossip column phalluses (everybloodyone, especially Visage), Talk Talk stayed sullen and strange and made mildly marvellous albums which saw them weaning themselves away from all the other clowns in the pop circus.

By 1988's 'Spirit Of Eden' LP, the weirdness was absolute. Conscientiously rejecting all the handy tips on How To Make Records, Talk Talk booted themselves onto the touchline of the left field by making the kind of album which gives product managers ulcers, and then threw a few gallons of four star onto the flames by taking a rather early retirement from touring.

"Even at the time of 'The Colour Of Spring' (1986) it was getting increasingly difficult to play the material live" says Hollis, with a surprisingly cock-er-nee tinge. "We were looking at rearranging songs, but having spent a year and a half making the record, the LAST thing you want to do is go back in and rearrange it ! There's a lot about playing live that I've never got on with, but I do think it's really important, and I'd hate to give the impression that I think all bands should be studio-bound."

Not surprisingly, the band's long-term relationship with EMI found itself aground on rocks the size of Norway. Even less surprisingly, when Talk Talk tunnelled through a loophole in their contract and out into the daylight at Polydor, EMI started ransacking the vaults and flogging old Talk Talk hits by the pound. The band were helpless to act when a Greatest Hits package sent them soaring into the Top 20. But when a crass compilation of dance remixes was released to cash in on Talk Talk's odd, unwitting relationship with Club Culture, Hollis finally sent in the lawyers.

"I've never heard the stuff and I never want to," scowls Hollis. "I never even considered that anyone would do that type of thing. To have work put out under your name which has got nothing to do with you..." the singer tails off, looking profoundly exasperated. "I mean, we were nominated for Best Band at the Brits last year and they were showing footage of us from 1983, with absolutely no regard for what we're doing now."

The important thing is that, excepting imminent court cases and several thousand deceived punters wandering around in the belief that Talk Talk are a bona fide pop act, Mark Hollis has landed on his feet. Polydor have resurrected the old Verve jazz label for the band, and the new 'Laughing Stock' album sees Talk Talk cruise even further into their own vague otherworld.

With its middle names of Abstract, Obtuse, and Damn Bugger Weird, 'Laughing Stock' is a six-track meander through calm territories littered with easily aggrieved volcanoes of sound.

Hollis denies that any particular 'theme' has prevailed over the past eight years, but when the word 'organic' - bandied around Talk Talk's press file like shouts of 'tits' at a rugby club karaoke night - stumbles into conversation, the singer's eyes light up with the luminosity of a fireworks display.

"Organic is a really nice word, basically because it means natural. What you see is what you get. The thing that anyone wants to do is to create something that exists outside of the time it was created in. And the only way you can do that is to work without sounds that are stylized, work with them in their most basic form. Part of what I like about sound is that quality isn't down to size, it's down to its idiosyncrasies."

There's certainly no shortage of them with Talk Talk. What is ironic is that, while their sound is in virtual free-form, the composition is maddeningly painstaking.

"That's a result of having stopped touring and just having an open-ended amount of time." nods Hollis. "It wasn't like we've got six months to get it all done and then tour again, it gave us the chance to try anything, and not care if you get 100 musicians in and only use one of them."

So speaks an artist from the luxurious heights of a five-star deluxe pedestal. With a bidet. And big, fluffy dressing gowns. Like The Blue Nile (only a bit more unsettling), Talk Talk have worked themselves into a position where they can do what the bugger they like without fretting about deadlines or panicking about people's perceptions.

They're making (theoretically) Q-generation music for the thirty- somethings, who'll tap their toes erratically and think 'Laughing Stock' is fab simply because it's the latest Talk Talk CD, while obscure teenage collectives like Bark Psychosis have taken Talk Talk's creative rumblings to heart.

Talk Talk genuinely deserve to be where they are now. The good thing is that Hollis, far from evolving into a blinkered farthead, is fully aware of the benefits.

"I think of us as being in a fortunate position here," he frowns, snuggling into the sofa. "But I wish more band were in this position; everyone would benefit, certainly the public and the bands, and at the end of the day record companies would do no worse."

Suggest that music is a cry for help and Hollis will holler "Cor, no !" in a thoroughly shocked manner, like an Eastenders extra. For all the extremes tested by Talk Talk's sound, this is no emotional outlet for an angst-ridden talent quivering on the edge of a nervous breakdown.

"I don't know whether that's necessarily true anyway. You don't need to be a manic depressive to write your best stuff. I'm sure that's just a myth."

He beamed....

"Yeah, that's right! Hahaha! Very good!"

^ go back to topMelody Maker: October 26th 1991

For every minute of music you hear on Talk Talk's new album, 'Laughing Stock', there's an hour of music abandoned. Cliff Jones talks to Mark Hollis and engineer Phill Brown about how it was pieced together.

Talk Talk, like a wayward but brilliant child, are out to test the patience of their public once again. Their fifth studio album, "Laughing Stock", sees Mark Hollis and his band of sniggering cohorts pushing things as far as they dare before the teacher's ruler descends on their collective necks and brings them back into line.

With the delicate free-form beauty of 1988's "Spirit of Eden", Talk Talk isolated many of the fans they picked up on release of the million-selling "Colour of Spring". "Spirit…" was considered by many to be too cryptic, too awkward for mass consumption.

Disappearing into the studio in November last year having left EMI and signed to Polydor's Verve label, they returned seven months later with a record that picked up where the former left off. It refined the sound collage technique almost to the point of abstraction, a series of fragile ambient soundscapes.

The criticism now levelled at Talk Talk is that "Laughing Stock" is little more than a side step, an attempt at avoiding the issue of where to go next, and as such certainly can't be seen as a progression. For Hollis, though, it represents the opposite, the development of the theme pioneered on "Spirit…" to its conclusion. As for alienating their public…