Mark Hollis

- The Colour of Spring

- Watershed

- Inside Looking Out

- The Gift

- A Life (1895 - 1915)

- The Daily Planet

- A New Jerusalem

The Wire: January 1998

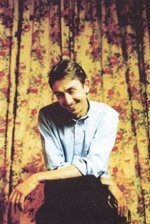

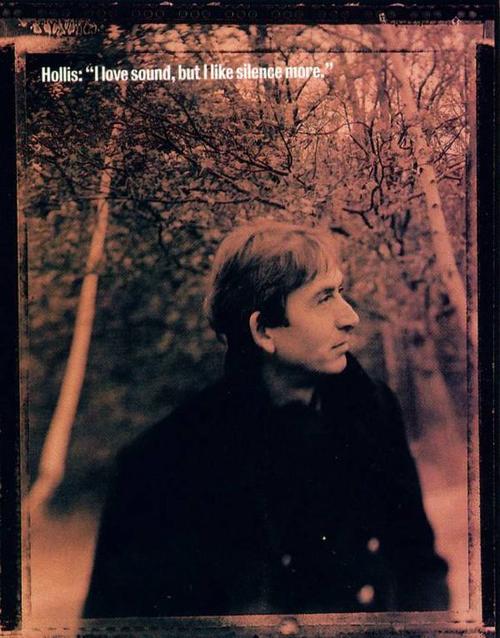

As the prime mover behind Talk Talk, Mark Hollis threw off the shackles of a pop existence to create the bleakest, yet most lyrical orchestral rock this side of Scott Walker. This year he breaks a seven year silence with a brand new solo album. Words: Rob Young,

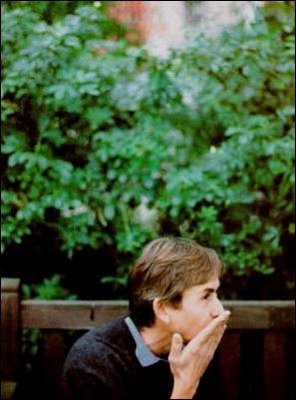

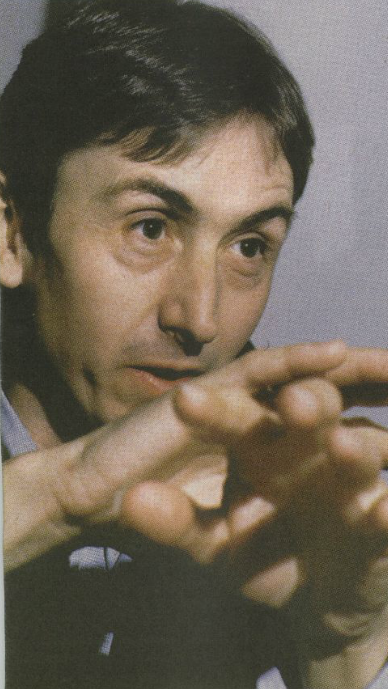

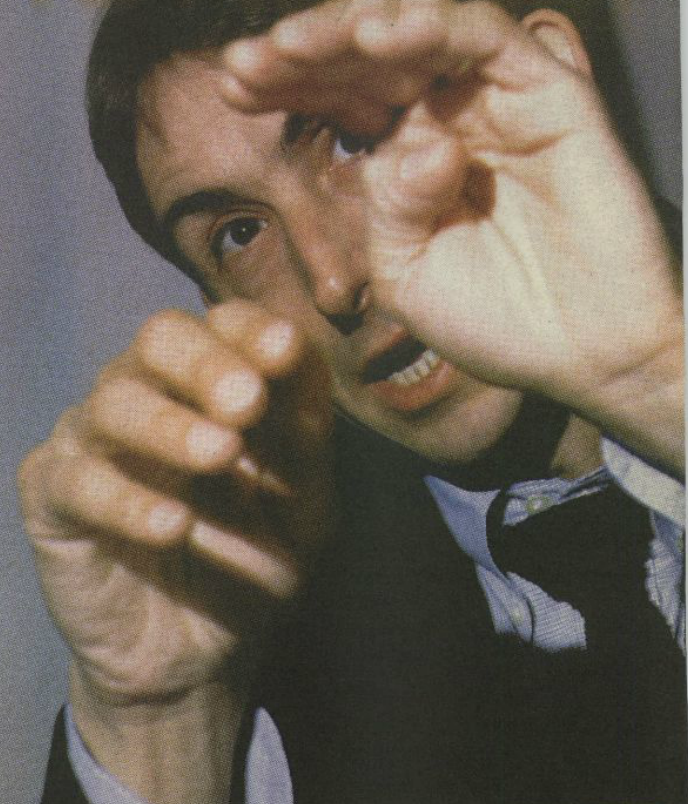

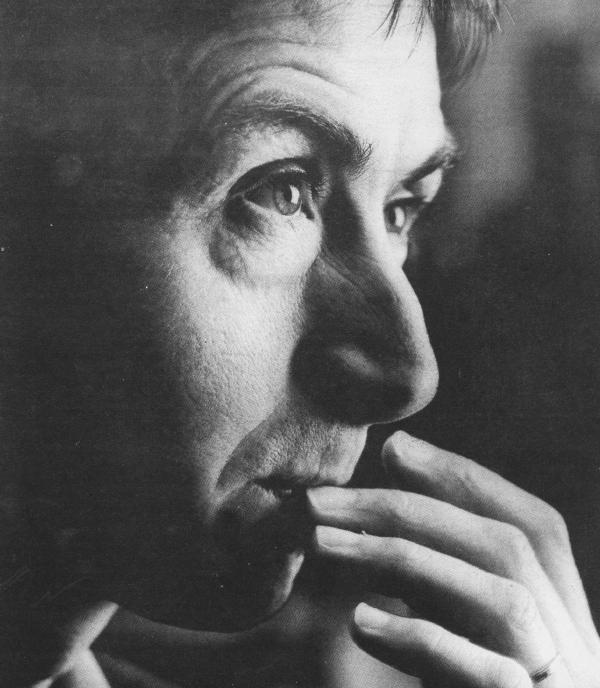

Thrill has gone. Back from the wilderness, back to the circus. Film demands your image: photographers lead you into the cold. Writers keep you hanging around. You don’t want to be doing this. You cover your face with your hand.

“At the point when you finish an album,” Mark Hollis is saying, “the last thing in the world I could think of doing is start writing another one. At the point where you’ve made it, that says what you want to say at that point in time, so it’s not like the next day you can begin another one”.

Anyone whose ears were pruned and re-rooted by the last three Talk Talk albums should make the most of Hollis’s new, self-titled collection of nine songs. It’s been a long time coming - seven years, in fact, since the great white spaces of the fifth (and, it transpires, final) Talk Talk album Laughing Stock - but unquestionably worth the wait. Deceptively simple acoustic surfaces shimmer with all manner of spring-loaded detail, choked and wrenched vocal performances, miniature symphonies of wind instruments, and references to the recording process itself (at times, the creaking of Hollis’s guitar stool is louder than his singing; at others the oral noise from his mouth makes you wonder if he had the mic down his throat). Perhaps as a reaction to the big budget, commercial suicide productions of late Talk Talk - Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock - Mark Hollis was recorded with a minimum of flash.

“Yeah, well the thing about that is,” Hollis explains, “everything’s just recorded off this pair of mics at the front, vocally as well. The reason I like the idea of that is, you’ve got the whole geography of sound within which all the instruments exist, but if you listen hard enough, you can actually hear where my head’s moving in position as I’m singing. Because it does exist in a real room space.”

The musicians on the new album include pianist Phil Ramekin, guitarist Dominic Miller, drummer Warne Livesey and a wind quintet; while Phill Brown has taken over the producer’s chair from Tim Friese-Greene. They don’t add much to the model established on Laughing Stock - drummer Livesey provides deadringer equivalents to Lee Harris’s damped snares and ringing ride-cymbal mosaics, and the music palpably breathes - but there is a continuity here that leads back to the jagged edge at which Laughing Stock tore Itself off after 40-odd minutes. “Cor!” he replies (his response to any mildly heavy question), “well, all that I can really say is that from album to album, you want to actually make a development, otherwise what’s the point of recording it?”

Given that the majority shareholders in the future of music are those involved in offshore deals with dance music, Hollis’s new offering is a brave and unworldly return to active service. Press material sent out with the record fashionably namechecks Stockhausen and Miles Davis, but I hear neither: Morton Feldman seems a much closer presence. Hollis is not known as a volatile interviewee, but that observation hits the jackpot

“Yeah, Morton Feldman is a total winner,” he says, sitting on a park bench in West London - the only situation in which he’d allow himself to be photographed. “There’s one particular thing called The Viola In My Life Part 2 - what I really love with that is, for me, that’s the closest thing I’ve ever come across that I feel I identify with; not only for its Minimalism, but the actual level at which he hits the notes. He’s as much interested in the tonality of the instrument as he is with the note itself, and that’s really important to me.”

Many points on the album seem to achieve the ultra quiet ppppp dynamic that was Feldman’s speciality. “Yeah, it is extremely quietly recorded. On “Westward Bound”, that is without doubt the quietest I’ve ever done a vocal. I could barely even get a sound to come out. I really like instruments hit at low level, and like I say, given the point that everything is playing at that level, you’ve got to be in sympathy with it.”

The album is seasoned with weeping woodwind interruptions, testimony to Hollis’s exploratory listening habits over the intervening years since 1991. “There’s so much out there to listen to, and that takes all my time. For me, the best of that earlier bunch of composers that I’ve become aware of was Ravel, who I only ever knew for the Bolero, that hideous piece of work - and yet you’ve got stuff like his String Quartet, also his music for poems by Stephan Mallarmé, which are just a fantastic bit of writing and arranging. So it’s like meandering along these little avenues and listening to stuff. That’s how it works for me.”

Nothing on the album is electrified. “The minute you work with just acoustic instruments, by virtue of the fact that they’ve already existed for hundreds of years, they can’t date. When you’re looking at writing music, the ideal must be: I’d like to make music that can exist outside the timeframe. So your biggest chance of doing that, I guess, is working with instruments that by their nature don’t exist in a time period. So, no syndrums - great as they were ...”

“Saw the bridges that I burned “ - “The Colour Of Spring” (1998)

Routes to the loot, part one: allow a major label to hammer all your quirks, noise, mistakes, inspirational innovations, ‘uncommercial’ sounds, arhythmic breakdowns, unsummarizable sentiments, into a conveniently marketable musical krush. Let market forces be the sandpaper that stops you chafing. If that’s what pop groups are supposed to do, Talk Talk did it wrong. They began (in 1982) happy to be moulded as an airbrushed, prinking-and-preening pop outfit, but gradually extricated themselves via the committed pop of 1986’s The Colour Of Spring, which wheeled in Traffic’s Steve Winwood’s Hammond to burnish their granular grooves. Then came the big jump: Spirit of Eden, the album classed by some as an Astral Weeks for the 80s. In the climate of nostalgia, irony and postmodern mimickry that characterised the culture of the times, the record pricked the bubble economy of the Thatcher years like no other. But was it made for the same reasons that caused the group to form in the first place?

“Cor! No, no, at the point when I first started,” he says, “It was because I just loved records. And I really wanted to be in a band to make music. And then when we first started, the kind of stuff I was listening to was obviously very different to the stuff I’m listening to now. And you’ve got this thing where from album to album you want some kind of development, but at the same time in order to get development and not to hit repetition, you constantly come across things which you think, yeah, I can do that if I do It the way I’ve already done It, but I don’t want to do it that way. And that, I think, is what forces you into other areas. You see, through these albums, for me, each one has felt like a very natural progression from where the one before was. But from this one to the fIrst one, there’s no relationship there at all.”

Did something particularly significant happen between the making of The Colour Of Spring and Spirit? “No, I think at the point we got there, Spirit of Eden was very much felt like where it was always kind of heading, but no, nothing ... More than anything, it was just not wanting to repeat what you’ve done. All the time, you’re getting older and everything and nothing is static It feels far more bizarre to me that there should be no change. That feels really very weird to me.”

“Makes it harder more you learn “ - “The Watershed” (1998)

Look back over the lyric sheets in the very first Talk Talk albums, The Party’s Over (1982) and It’s My Life (1984), and you’ll find the word “change” repeated passim. Although stylistically those records are likely to remain locked in time, with their Simmons drum pads, bendy synth solos, guitar synthesizers, Fairlight sequencing and Athena poster-style paintings by James Marsh, there weren’t many pop groups at the time capable of confessional stanzas like “Happiness can often bleed/Beggars lay among the sheep/Let me take the choice/The sermon pleads”; “Take this punishment away Lord/Name the crime I’m guilty of/Too much hope I’ve seen as virtue/Name the crime I’m guilty of”.

Contemporaries like Duran Duran and ABC wrote puffed-up, straight-to-video poetic contrivances; TT were closer if anything to the earnestness of Tears For Fears, who later revealed they’d embarked on a pop career in order to fund their own psychoanalysis sessions.

Hollis and Talk Talk, though, never allowed themselves to slip into the smug certainties and flash lifestyles of the 80s pop nouveaux riches (they didn’t take part in Live Aid, for a start). Hollis’s early songs struggle with notions of fate versus faith, with imagery swinging from the Bible to Luke Rheinhardt’s cult novel The Dice Man. When the songs for which they’re best known, “Life’s What You Make It” and “Give It Up”, hit the charts in 1986, they sounded like Cassandra baying In the wilderness - a lone, moral voice railing against the backdating of experience by mass media exposure and the tragedies of drug abuse. On top of that, their own travelling circus became too much to bear, you could hear it in Hollis’s blasted shreds of vocal.

“Originally,” remembers HollIis, “I thought playing live was the best thing you could ever do. The problem when you hit nine month tours is, firstly, for nine months you’re dealing more with recreating the past than with looking into the future. You’ve also got this horrible thing where, despite the fact that you go through different countries and different cultures, you’re totally oblivious to them and you’re just shelled out against that. So that’s quite ugly; also within the day you’ve only got the one hour which is about performing and the rest which is obviously about very mundane things. The other problem when we hit that last tour was that the material was becoming increasingly hard, even with The Colour of Spring, to perform live. So even in that tour in 86, maybe two thirds of the material was based around the second album rather than the one we’d just finished making.

“And the other thing: I just think it’s really important if you perform that you actually mentally go where you’ve got to go, and to do that six nights out of seven is extremely wearing. The only way over a period of time, I could get to that, was to do a lot of drink. And I don’t think that is a good exercise” Were the anti-heroin songs inspired by personal experience? “No, not at all. But, you know, I met people who got totally fucked up on it.. Within rock music there’s so much fucking glorification of it, and it is a wicked, horrible thing, you know?”

“I don’t like to read the news/D’you know anything I’m going through?” - Have You Heard The News?” (1982)

After 1986, the three core members of Talk Talk became fathers. Hollis decamped to a farm near Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk (don’t call it a ‘retreat’: “I see things in terms of pursuit rather than avoidance,” he tells me), where he surrounded himself with a menagerie of domestic animals “Tons of ‘em, 18 at the peak, all running loose,” he recalls with a wry smile. (He’s recently moved back to South London: “That was just because I’ve got children, and I just wanted my eldest one to be aware of the culture that exists.”)

In this rural setting work began on the music that would usher in the second phase of Talk Talk’s development Spirit Of Eden. When they emerged, blinking briefly in the light, the cosmetics had been kicked down the same chute as the synths, syndrums and trite rhymes. “The world’s turned upside down”, sang Hollis over a blaze of amped-up harmonica and Henry Lowther’s muted trumpet. With an augmented lineup that included Danny Thompson on double bass, percussionist Hugh Davies, classical clarinettist Andrew Marriner, Nigel Kennedy on fiddle, and the Choir of Chelmsford Cathedral, and tricked out with a humanist/ecological/holistic ‘message’, this was a full-scale rock Passion that picked up critical acclaim, but permanently destabilised the group’s relationship with EMI. Three years later, the company retaliated by shunting out History Revisited a quick-fix dance remix album assembled without the group’s consent.

Spirit closed with the line “Take my freedom for giving me a sacred love” - it sounded like Hollis had been boning up on the renegade, mystical Christianity of William Blake. The thread leads through to the new record, with its references to “A New Jerusalem”, redemption, purification, blood, repentance and atonement. Astonishingly Hollis cries ignorance of Blakels work. “I’m not a born again Christian, no,” he says. “But I would hope there’s a humanitarian vision in there, for sure”. So where does that elliptical imagery derive from? “If I think of favourite films of mine, what they deal with is character and virtue, they don’t deal with narrative. That’s a very secondary thing. The two films I would think of more than anything would be The Bicycle Thieves and Les Enfants Du Paradis.” Curiously I had seen The Bicycle Thieves only the week before. “It’s fantastic, isn’t it?” he says, animated. “What happens? A bloke gets his bike nicked. But it’s all there - just amazing. And the emotion in the end, with the little kid, when his Dad gets tugged [for stealing a bike]: it’s all there, really strong.”

Like the the film’s anti-hero Hollis had his most treasured possession stolen from under his nose when EMI remixed the soul out of his precious music. The writ that subsequently hit the fan 1et to the record being buried, but the process cost the group’s future. He says he’s enjoyed the two albums former members Lee Harris and Paul Webb have since released as .O.rang, but admits that they’ve stopped playing together. “I don’t see them any more,” he says. Why not? “I’ll tell you if you don’t print it.”

“The good has bled to dust” - “The Watershed” (1998)

Touch Hollis for an explanation of his new songs’ thematic content, and you’ll encounter a thick hide. He won’t be printing the lyrics on the sleeve, and If you can decipher more than a third of the words on the recording, I’ll sell my ears. Like the posthumously released, harrowing demos of Nick Drake, John Martyn’s Celtic psychedelia, or Robert Wyatt’s keening treble, Hollis possesses one of the great unrock voices. It’s all whisper and no scream: at times, the voice is little more than a thin parting of the air in the studio; the words are stretched out, torn apart, boiled down to consonant acoustics. “With lyrics,” he says, “they’re totally important in one way, but equally they’re not of any importance at all, because they’ve got to be secondary to the actual way the thing moves phonetically. When Malcolm Mooney was singing with Can, he invents his own language, and does it in a way that doesn’t sound contrived or Stupid. You don’t think he’s gone into Toytown land or something ...”

Like Mooney, Hollis loads elliptical verse with apocalyptic weight. The timescale referred to in the album’s incredible centrepiece, “A Life (1895-1915)”, spans the turn of the century 20 years in which the Victorian Age got trampled into the mud of the trenches. “The dates were taken from ... it is the First World War and it’s just that at the time I read a few books about that period, like All Quiet On The Western Front, Testament of Youth; and I think those dates - I might be wrong, but I’ve got a feeling they were Vera Brittain’s boyfriend. It was more that idea that you’re only one year into it and then you’re topped.” The reference to “A New Jerusalem”, meanwhile, is “much more tied up with two things, when I thought about it that was the way they talked about 1946; but equally, I thought: whether you’re back from Vietnam or whatever, it’s just that conflict between expectation and reality.” It’s an emotional state Hollis is adept at expressing in his music. Does he look for epiphany in such moments? “I don’t know I think of it being to do with compassion, if you like. It’s a tricky one. But you may well be right in what you say. You may well be right.”

Thrill has gone. The party’s over. And, once again, the future’s bright.

^ go back to topRecord Collector: January 1998

The ex-Talk Talk singer/songwriter has returned. This time he’s going it alone. But where has he been? Asks HAYLEY BARTLETT

Piano-pop gods Talk Talk jangled their way through the last decade with hits like ‘Today’ (1982) and ‘Life’s What You Make It’ (1986). After a seven-year break, frontman Mark Hollis has returned, with a self-produced and co-written solo album. File this one under your ‘Interesting Easy Listening’ section ladies and gentlemen. As an attempt to produce an eclectic hybrid of jazz, folk, and country, ‘Mark Hollis’ has come up trumps.

As a teenager in the 70s, Mark grew up with two great influences in his life. Older siblings are always influential and big brother Ed Hollis was no exception. As manager and producer for Eddie and the Hot Rods, he was to introduce his little brother to the wonderful world of music, as Mark confirms : “Ed was an extremely important influence, even before the Hot Rods. He was such an intensive collector of albums, he educated me in different forms of music.” The Hot Rods were also important because of their links with the phenomenal punk movement: “It’s the most important musical thing that has ever happened in my lifetime. There was so much emphasis on enthusiasm and energy - as opposed to ability. To me, the possibility of being in a band was so remote, but that whole movement opened it up.”

Hollis started his pop path in 1978 fronting new wave band the Reaction. A one-off 45, “I Can’t Resist” (Island Records), is now a modest hit with revival collectors. It was in 1981 that Ed introduced Mark to some session musicians he was working with - Lee Harris (Drums) and Paul Webb (Bass) - who, along with Simon Brenner on keyboards, formed Talk Talk. Stints supporting those glossy Duran Duran boys led to the gang gaining relative success with albums “The Party’s Over”, “Spirit Of Eden” and “The Colour Of Spring”.

For Hollis, the 80’s is a phase best forgotten. The electro-pop music of Talk Talk was recorded in what feels like a different lifetime. Sixteen years down the line, Mark has developed a passion for the quieter side of life. He’s also oblivious to what’s been going on music-wise for the past seven years: “With such an incredible wealth of music being made over the years, you don’t need to listen to contemporary music”. But what’s he been doing since the demise of Talk Talk ? Well there’s no saucy scandal, and no mammoth project to speak of, just a few woodwind pieces written for personal pleasure and a few years working on the new album.

The album is heavily influenced by jazz, and has a disjointed feel to it - a feeling that makes sense in an incoherent kind of way. Has he always been an admirer of the old jazz masters ? “I’m a real fan of the late 50s/mid 60s jazz, especially Miles Davis and Gil Evans. Two albums, “Porgy and Bess” and “Sketches of Spain”, were important to me. They had a good balance between looseness and careful structure.” Hollis acknowledges that during different periods you get into different areas of music and, as he explains, “elbow stuff along the way”. He wanted his solo work to have a very real sound to it :”I needed it to feel calm, to be absolutely minimal and to work with space, as much as you can work with space.” The theory behind the man is not to do anything unless there is a reason for it.

Hollis has co-written the album with pianist Phil Ramekin, guitarist Dominic Miller, and Warne Livesey, whose previous credits include Julian Cope, Midnight Oil, and Deacon Blue. With all these people approaching him for work, does he feel there was that sense of control missing with Talk Talk ? “Absolutely not, as a producing role didn’t really exist for me then. Where I am now is very distanced to where I began and I’m glad of that. Not because I’m bothered by anything that I have done, but I have moved on.”

There won’t be any live sets showcasing the new talents of Hollis, as it would apparently be impossible to perform live : “To get the instruments to balance, nobody would be able to hear them.” When asked about the first single from the album, Hollis smiled a knowing smile : “What is a single ? Something you boil an egg by ?” A fair point. So there won’t be any singles from Hollis, merely a delicate collection of laid-back vibes - the perfect musical accompaniment to a lazy Sunday afternoon.

Yes, Mark Hollis really does believe that life is what you make it. For him, it’s a quiet one, one filled with good music made with good friends, for no other reason than because he wants to. You get the feeling that it’s really quite an honour that we will ever hear it at all.

^ go back to topLes Inrockuptibles: Janvier 1998

Avec Talk Talk, Mark Hollis traîna longtemps le boulet d’une jeunesse pop frivole et nunuche. Désormais en solo après sept années d’absence, il revient avec un premier album, Mark Hollis, à la beauté et aux silences assourdissants.

C’est beau, un type qui a signé la paix avec ses nerfs, paraphé un armistice sans déshonneur, sans fermer les yeux. C’est apaisant comme une aube de printemps, un type comme ça, allégé, dégagé de ce angoisses mesquines qui, ailleurs, gangrènent et grignotent la petite vie des homes. C’est rare et rafraîchissant, un musicien, après sept ans des silence, ne soupçonne même pas qu’on ait pu l’attende au tournant. Mieux; un musicien qui, d’un pas serein, sort de sa retraite sans imaginer un seul instant qu’il puisse y avoir là un tournant – et des embûches, risques de verglas, dérapages potentiels.

Mark Hollis est étonnant de simplicité et de bonhomie lorsqu’on lui apprend que des congénères aussi estimables que Divine Comedy ou Labradford, pour n’en citer que deux, ont épié son album comme d’autres guettent en tremblant le prochain atterrissage du Messie sur la Terre. Les noms de ses fervents admirateurs ne semblent pas lui évoquer grand-chose: “J’ignorais que tous ces gens avaient adoré Laughing Stock, qu’ils espéraient que je redonne plus vite signe de vie. Et vous êtes sûrement mieux placé que moi pour mesurer l’influence qu’a eue le travail de Talk Talk…Vous savez, je ne lis pas la presse musicale. J’ai bien quelques amis musiciens, mais...Enfin, je suis flatté, très heureux, d’apprendre tout ça”

Modeste sans afféterie, Hollis accueille les compliments avec un politesse exquise et une absence quasi totale d’excitation. C’est n’est pas pour récolter des tonnes d’éloges ou pour moissonner des champs de gloire qu’il est ressorti de sa tanière. Probable que l’accueil enthousiaste qui lui sera réservé ici ou là lui ricochera un peu sur le paletot. Surtout ne pas s’en offusquer, ne pas crier à l’ingratitude. Simplement, tout cela est loin du Cœur même de la musique, de cette région où Hollis, il y a quelques années, s’est efforcé de s’aménager un coin d’existence, à l’écart des courants de mode et des agitations de l’industrie musicale. Chez lui, le besoin maladif de reconnaissance, la course aux médailles en métal ou en chocolat, le souci de chiader son image sont autant de bêtises depuis longtemps parties en fumée, évaporées dans ce qui restera l’une des plus passionnantes métamorphoses et libérations musicales de ces dernières années.

En un peu plus de quinze ans, Hollis a réalisé un tour de passe-passe peu fréquent: se rendre à la fois essentiel et invisible. Ce que quelques commentateurs amis de poètes auront résumé par ‘suicide commercial’. Manière comme une autre, après tout, d’analyser l’atypique cheminement de Talk Talk. Ou comment, en moins de dix ans, un popband propre se sera associé benoîtement à la rumeur du monde (The Party’s Over 1982) fondu dans le grand concert des vanités (It’s My Life 1984) pour finalement s’en retirer progressivement (The Colour of Spring 1986), se jeter tout seul de l’établissement (Spirit of Eden 1988), se mettre définitivement hors compétition (Laughing Stock 1991) et finir en beauté, grillé, inclassable et ineffaçable. Cette marche en avant vers la plus irréductible des singularités, Mark Hollis en aura été le principal artison. Cet homme n’est ni un inconscient nu un ahuri tombé de la lune, encore moins un moine fou. Juste un chanteur-compositeur d’une calme lucidité, découvrant au fils des années qu’on gagne beaucoup a pratiquer des soustractions et a désapprendre certains certitudes.

Si l’on excepte le cas de Scott Walker – voire de Leonard Cohen ou de Robert Wyatt – il est rare que le besoin d’oubli, la quête de vide et la compagnie du silence nourrissent ainsi un homme, enrichissent autant son histoire, élargissent sa vision. Le résultant, c’est qu’aujourd’hui Mark Hollis, ce solitaire qui semblait ne plus y être pour personne, signe plus que jamais sous son nom une musique qu’aucune autre n’égale. L’Affaire, on s’en souvient, sera pourtant partie sous de bien pauvres auspices. Pas chanceux, Mark Hollis, Lee Harris (batterie) et Paul Webb (basse) créent Talk Talk à l’aube des années 80 : on est alors en train de ranger définitivement le joyeux foutoir des deux décennies précédentes et d’enterrer les derniers ossements punk.

L’époque, gonflée, se proclame sans rire new-wave. Le rock anglais, qui semble partagé entre deux épineux choix esthétiques - se peindre l’âme en noir ou se teindre les cheveux en blond – tient autant du caisson réfrigèrent que du salon de coiffure. Sur leurs deux premiers albums, Hollis et les siens, nourris, peignés et habillés par leur maison de disques, moulinent une techno-pop au pompiérisme policé, plutôt engoncée dans ses vêtements synthétiques : c’est le temps de Such a Shame, de It’s My Life, sur lesquels le jeunesse d’alors use pas mal de mocassins. Malgré les textes mystérieux d’Hollis, de timides étincelles d’originalité et la présence aux manettes de Tim Friese-Greene, futur grand architecte du groupe, rien ne distingue vraiment Talk Talk des caniches néoromantiques qui jappent alors leurs chansons-bluettes dans les charts.

Avec The Colour of Spring, le groupe amorcera un premier (petit) virage sur l’aile. C’es un édifice au style encore un brin mastoc, bien assis sur un emboîtement de tubes en béton – Life’s What You Make It, Living In Another World – mais, où Hollis laisse déjà apparaître de belles fissures. Ainsi April 5th et Chameleon Day premières landes musicales d’inspiration plus minimalistes, sur lesquelles le silence tombe en flocons. Peu de temps après, le groups décide de ne plus se produire sur scène : manière d’annoncer qu’il va bientôt prendre congé de son époque.

« Notre dernier concert dates très précisément du 13 Septembre 1986, en Espagne… Je savais que c’était le dernier. J’avais deux enfants, il me paraissait totalement inconciliable d’être à la fois père et musicien en tournée. Mais c’était aussi un choix artistique. La formule album-concerts-album-concerts n’apportait que frustrations. Je ne voyais pas l’intérêt d’aller pendant des semaines rabâcher nos chansons sur scène. : une fois un disque achevé, mieux vaut bouger, avancer. Ou alors il faut avoir le génie d’un groups comme Can, capable de se redéfinir en concert, de bouleverser la donne chaque soi… Selon moi, Talk Talk a toujours suivi une évolution très logique. Mais c’est vrai qu’il y a eu une rupture à ce moment-là : nous sommes sortis d’un engrenage. Grâce notamment au succès de It’s My Life et de Life’s What You Make It, nous avons pu prendre nos aises et notre temps, et tenter l’aventure de Spirit of Eden.

On imagine les vertiges du fan découvrant ce dernier, se confrontant aux vingt-trois minutes de The Rainbow : c’est une crevasse que Talk Talk, aven une maturité dans l’audace inattendue, ouvre en plein milieu de son univers pop. Un gouffre dans lequel couplets, refrains, rythmiques trop carrées et arrangements trop pleins disparaissent corps et biens. Deux ans seulement après The Colour of Spring, le trio solde brutalement le compte d’une jeunesse trop polie, abandonne définitivement toute corvée inutile et se dote d’un langage musical à la fois cohérent et joliment évasif, réfléchi et dicté par le hasard. Les synthés sont remplacés par des parents plus discrets et moins pauvres – piano, harmonium, orgue. La batterie d’Harris est démantelée, cesse de réciter son Encyclopédie en dix tomes, sauve ses cymbales in extremis et ne s’exprime quasiment plus qu’en sourdine, soupire, murmures. La guitare ne délivre que quelques timides impulsions électriques, la basse n’est plus en plastique. La voix, lézardée s’offre déjà en lambeaux. Des instruments à vent laissent entendre leurs premières respirations, un violon frémit. Et on renonce à asperger le son de laque, à l’enfouir sous des couches de réverbération vernis. Le grand vainqueur, naturellement, c’est le silence : nouvelle éminence grise, il se tape là ‘lune de ces invisibles incrustes dont il a le secret, investit l’ombre et gagne l’avant-scène, semble prendre chaque note en sandwich, pose des coussins d’air derrière chaque instrumente et tire sans vergogne sur la corde du temps, ce vieil élastique incassable.

A l’époque, une rumeur idiote se répand : Hollis et les siens, dit-on auraient réveillé le fantôme de la musique progressive, ressorti du hangar la vieille machine à planer – un pur acte d’inconscience, en somme. En Angleterre, où l’on se redécouvre alors une passion pour les petits coucous de la pop, les chansons qui pètent le feu et les refrains loopings, les figures libres et amples de Talk Talk inscrites dans un ciel inédit, détonnent. Déjà isolé et pas malheureux de l’être, le groupe, qui a rompu avec son ancienne maison de disques, effrayée, largue définitivement les amarres avec Laughing Stock : un sommet de dépouillement et d’invention, bourré de nuances et de vitalité, brouillant les frontières entre l’écrit et l’improvisé, l’un de ces crimes parfaits, accomplis avec le calme des grands assassins. Est-ce encore du rock ? La question surgit, qu’on s’empresse du juger sans importance. Pour Hollis la vie est ailleurs, dans une constante redéfinition de la composition, du son et de l’interprétation, qui annonce déjà d’autres expériences sur la matière : a Chicago, à Bristol ou ailleurs, partout où l’on s’apprêtera à faire valser les étiquettes et trembler les vieux cadres, les noms de Talk Talk et de Mark Hollis circuleront bientôt comme autant de mots de passe, fédérant et stimulant les plus frondeurs des apprentis sorciers.

Après Laughing Stock, j’ai pensé que le groupe avait intérêt à se séparer et qu’il fallait mettre fin à la collaboration avec Tim-Friese-Greene. Je sentais que tous ensemble, nous avions atteint une limite : pur continuer le voyage, il fallait se relancer seul…Ensuite, des années ont passé avant que je ne m’attelle à cet album solo. Mais enregistrer un disque, au fond, ce n’est pas une ambition première. L’accomplissement, c’est quand même ce plaisir jamais entamé de jouer – le punk, auquel je resterai toujours attaché, m’a transmis cet enseignement très simple. He joue à peu prés tous les jours chez moi et je n’ai aucunement l’ambition de tout fixer. Je peux passer des heures devant mon piano, à explorer les propriétés acoustiques d’une pédale ou à caresser du doigt une touche. Ces moments d’intimité avec l’instruments m’a portent plus que si je m’astreignais à un travail d’écriture régulier et à un petit album annuel. Au fond, ce que m’intéresse le plus, c’est ce qui se passe entre deux disques. Ces intervalles où vous vous demandez comment développer encore davantage votre musique, bâtir dans la différence sans vous renier…JE ne peux pas concevoir un album si je ne suis pas assuré qu’il me portera plus loin que le précédent. Chez moi, ce travail de réflexion peut prendre un temps fou. Plus les années passent plus il y a de choses que je ne veux plus répéter, de similitudes à éviter. Et puis il y a aussi de nouvelles écoutes, des découvertes – depuis des années maintenant, je me passionne pour la musique contemporaine, j’ai perdu tout contact avec l’univers du rock et de la pop. Alors il me faut attendre, passer par des creux et des bosses, visiter beaucoup d’endroits avant d’apercevoir une nouvelle direction à suivre. Petit à petit, une pertinence se dégage, la lumière se fait, il est temps de se lancer. Mais même après ça, je peux encore passer des jours entiers sur un passage qui, au final, ne représentera qu’une demi-seconde de musique sur le disque…’

On dirait que Mark Hollis répond à une force secrète. A une énergie indicible qui, depuis ses débuts, l’entraînerait irrémédiablement vers l’épure la plus radicale et la plus douce à la fois. Ainsi, à l’écart des fracas ambiants et des vocabulaires actuels, e-t-il décidé sur ce premier album solo d’explorer au plus profond la veine du tout acoustique et de visiter toute la gamme des silences musicaux. Sans préceptes de vieux sage chinois, sans leçons d’ancien combattant à la clé. Sa démarche, d’une fraîcheur et d’une finesse inouïes, n’est pas sans rappeler la magie pourtant sans exemple d’un Robert Wyatt : Comme sur Shleep, un artisan transmute en or pur des matières apparemment communes et bien connues, et nimbe d’une grâce nouvelle des gestes ancestraux. Le minimalisme de Mark Hollis ressemble à ces vielles gens qui, dans leurs masures délabrées, cache d’insoupçonnés trésors. Volontairement hors du coup, il réinvente et subvertit la chose musicale, la géographie des sons, la position du chanteur, parsème chaque pièce de grands écarts, dissonances, névralgies harmoniques. D’où une musique qui, sous des dehors familiers er sans obsession d’être à la page, semble déjà en contenir et en précéder d’autres.

« Je ne suis aucunement soucieux d’être moderne ou d’avant-garde. Je suis plus concentré sur mon travail que sur mon époque – c’est sans doute pour ça que j’aimeras qu’il lui survive. Il se trouve que l’électricité, l’amplification des instruments, ça ne m’intéresse plus. En revanche, j’ai toujours aimé la nature, la ‘voix’, la texture, l’infinie richesse des instruments acoustiques. Avec eux, par exemple, il sera possible de s’approcher de niveaux sonores démentiellement bas…avec Phil Brown, l’ingénieur du son, nous avons accompli un énorme travail de ce côté-là sans artifices, simplement en jouant sur le positionnement des micros, des instruments dans le studio. J’ai aussi essayé d’appliquer ça à ma voix. L’idéal, ce serait de ne plus changer les mots, mais de les penser tellement fort qu’on puisse les entendre…Je voulais que, comme chez Morton Feldman, l’auditer ait intérêt à ne pas écouter ce disque trop fort s’il veut en saisir toutes les nuances. Ce Qui est aussi l’une des seules chances de rendre au maximum la dimension spatiale de la musique : je rêve d’un disque où les gens, chez eux, localiseraient exactement l’endroit où se trouvait chaque instrument au moment de l’enregistrement. »

Ceux qui ne voient dans cette œuvre que figures en apesanteur et beautés diaphanes en seront donc pour leurs frais. S’il est poète, Hollis, - par ailleurs très au fait des réalités de ce monde – est moins un Pierrot lunaire qu’un explorateur des profondeurs musicales les plus fines, les plus intimes. Comme toute aventure spirituelle, sa quête sans fin, aussi intérieure soit-elle, se nourrit également de rencontres, d’échanges et de plaisirs bien concrets – et entend célébrer la dimension charnelle, physique de la musique.

« Comme beaucoup, j’ai un idéal de pureté : mais je ne le conçois que dans l’expression d’une vérité, d’une réalité concrète. Avec la musique, je palpe, je cherche, je sonde, j’interroge, peut-être pour essayer de traduire an mieux la matière même de l’existence. Dans le cadre d’un disque, ça signifiera intégrer aussi les erreurs, les détours inattendus, le tremblé, d’une voix ou le frottement d’un bras contre une guitare. Je ne cherche pas la perfection, qui m’ennuie, mais l’honnêteté. JE me fous par exemple des capacités techniques du musicien : son approche de l’instrumente m’intéresse davantage. Sue cet album, le pianiste, par exemple, est le professeur de musique de mon fils. Techniquement, il est sûrement loin d’être parfait. Mais sa relation à l’instrumente a énormément apporté à l’ensemble. Il accrédite parfaitement cette idée selon laquelle il est bon, avant de jouer deux notes, d’apprendre à savoir en jouer une. J’aime que les musiciens, que je laisse toujours totalement libres dans leur interprétation, n’oublient jamais leurs relations avec l’ensemble, avec chaque élément de cet ensemble. Il y a là une sorte de…géométrie qui amène la poésie. Sur cet album, j’ai notamment voulu explorer ça avec les instruments à vent. Des outils extraordinaires, auxquels je voue une affection particulière – et surtout la clarinette, qui est sans doute l’un des instruments les plus proches de la voix humaine. Sur cet album, il y a eu des moments de partage et de découverte incomparables…Dans ce genre de conditions, enregistrer ne peut être qu’une expérience apaisante, facile. Si le disque conne si calme, ce n’est pas seulement par choix esthétique : nous étions réellement, les uns et les autres, dans un grand état des sérénité. »

Après ça, qui osera prêter à cette musique des origines extraterrestres ?

Si ce disque semble détaché du monde, c’est surtout, qu’il est d’une implacable beauté, d’une cruauté inouïe pour ses contemporains. Sous son imperturbable tranquillité brûle un bûcher qui flambera pas mal de vanités : un art sans âge qui accélère le vieillissement déjà bien engagé de la majeure partie de la populations musicale. C’est aussi un disque qui, du coup, semble sans retour. A tel point qu’on demande finalement à Mark Hollis s’il ne craint pas d’avoir atteint là le bout d’une sublime impasse, un point final. Il sourit, répond sans ciller que oui peut-être, qu’il n’en sait rien. N’osant dire, sans doute, qu’il s’en fout un peu. Le temps ne joue plus contre Hollis et Hollis ne court plus âpres le temps. Comme si ces deux-là s’étaient rejoints, apprivoisés, mêlés, agissaient désormais dans le même camp, sur un même plan. Tranquillement souverains et pareillement insaisissables.

^ go back to topNME: 17th January 1998

Before we get to the heart of the matter: Mark Hollis used to be the singer in Talk Talk, a group who began their career as tie-tucked-into-shirts Duran imitators at the start of the ‘80s and ended it ten years later as the moodiest practitioners of avant-pop since Roxy Music.

Pop will remember them for a handful of classic singles, including the unimpeachably great ‘Life’s What You Make It’, but an army of fans, hooked on the sort of intensity that makes Kevin Rowland look half-hearted, have dug in for the long haul. Their reward, a cool six years on, is an album that finds Mark Hollis armed only with an acoustic guitar, a bagful of free-jazz arrangements and a set of mood pieces that will have old fans striding through Elysian fields of delight and Aqua fans running screaming.

Let us not be shy: the mood throughout ‘Mark Hollis’ is as prickly and strangely foreboding as it ever was. Where once, it seems, there were the occasional shards of light in Mark’s world, even on 1991’s valedictory ‘Laughing Stock’ album, here he assumes the mantle of musical Luddite, shunning the illusory tricks of technology for a stripped-bare authenticity and a heart-rending self-absorption which allows him to have song titles like ‘A Life (1895-1915)’ without the merest thought for what non-fans may make of it.

Musically, an opening ‘Colour Of Spring’ boasts a twanging acoustic and huge orchestras of silence, while elsewhere we get the occasional midnight pulse of bass and sliver of harmonica (a positively epic ‘The Daily Planet’), the odd tumble of jazz-club sleaziness (‘The Gift’) and Mark’s ever-swelling voice, forever too intent on creating the necessary mood to ever afford more than the odd glimpse of a recognisable lyric.

So idiosyncratic is the combined effect that to liken the entire 47 minutes to anyone (or even a single genre) would be to do it a disservice, but in terms of mood; there are shades of the disembodied folk of John Martyn’s ‘Solid Air’, the pop desolation of Radiohead’s ‘Fake Plastic Trees’, and even the yearning spaciousness of Jeff Buckley’s ‘Grace’, all enveloped in the sort of elegiac mood that quite clearly makes Mark a less than ideal candidate to organise the Millennium festivities.

Not so much a comeback album, then, after six years away, but a comedown album, free from the fleeting concerns of commerciality but built rather as a haunted symphony, as indefinable as time itself.

Be assured, then: this is strange and beautiful music.

(8 out of 10)

Paul Moody

^ go back to topThe Independent: 23rd January 1998

This may well turn out to be one of the albums of 1998, but as with all Hollis’s output since Talk Talk’s 1988 opus Spirit Of Eden, we won’t really be able to tell for another year or two, so diffuse is the music it contains.

That album and its follow-up Laughing Stock were often (erroneously) compared to Astral Weeks, a record whose textural depth they emulated, though not its passion. With Hollis’s first solo album proper, the process of diffusion continues further, with delicate, tentative settings based on acoustic guitar and piano, and serious, painfully sensitive vocals that often seem little more than prompts.

It certainly bears no relation to rock’n’roll, but instead seems to aspire to the condition of classical music, with the enigmatic, faintly quizzical wind arrangements of tracks such as “A Life (1895-1915)” and “The Daily Planet” particularly reminiscent of the open, asymmetric patternings of the American minimalist Morton Feldman.

Like Feldman, Hollis prefers to let his melodies accrete over time, like dust settling, rather than be forcefully stated. The results play strange tricks with time: though few of these eight tracks last under five minutes, they barely seem to have begun before they’re finished.

^ go back to topThe Independent: 24th January 1998

The first album by the former songwriter and vocalist of Talk Talk - after a seven-year lay-off - isn’t quite what you’d expect. The full-blooded arrangements of oldies including “Life’s What You Make It” have given way to skeletal melodies, so Hollis’s emotional deliberations are very naked. Sometimes gospel power is with him, but mostly he appears very unsure of himself.

^ go back to topThe Sunday Times: 25th January 1998

ANDREW SMITH meets the former Talk Talk singer whose haunting new album marks the next stage in an intriguing musical odyssey.

There have been stranger lives in pop, but few more peculiar musical journeys than Mark Hollis’s. Hunched over a pint in a pub on a cold afternoon in Wimbledon Village, south London, his high voice will strike anyone who ever turned on a radio in the 1980s as familiar - this despite the fact that it has scarcely been heard in public for seven years. For Hollis began that decade as singer with the synth-pop group Talk Talk, the poor new romantic’s Duran Duran, and ended it as singer/composer with a combo powerful and imaginative enough to make The Spirit of Eden, a wholly new kind of rock album that owed more to Miles Davis than Madonna, or even Prince. Bizarrely, that combo was also called Talk Talk and the price of their post-rock adventures was forfeiture of their enormous commercial success and an acrimonious dispute with their record company.

On the other hand, few records made in that era have endured so well as The Spirit of Eden, just as few current albums will endure so well as Mark Hollis’s new, eponymous solo album. In its quiet way, Mark Hollis, the record (out on February 2), is as radical and innovative as anything by Goldie or Spiritualized. What’s more, seldom has such a successful “pop” record been less rooted in its time. Like Radiohead’s OK Computer, there is nothing to tie this music to 1998. Modern classical buffs will recognise something in the structure, instrumentation and shifting harmonic content of the pieces here, while jazz fans will be drawn to the lithe, lingering, free spirit of the playing. Those raised on pop will warm to the soul in Hollis’s surging, melancholic voice and the compactness of the arrangements. And if such a description makes Hollis’s project sound drily academic, now is the time to point out that the chief virtue of his work is its striking, understated beauty. There is no question but that it will be in my top 10 albums of the year, come December.

Looking thinner and more frail than he last did, dressed in a blue jumper of the type junior school boys wear with shorts, the reasons for Hollis’s absence soon become clear. Softly spoken, with his broad Tottenham accent sounding as fruitily at odds with the rarefied nature of his music as it ever has, he describes sitting at a piano hitting a single key for four days on end, listening intently to the special cadences of the sound draining from a dying string. He will also enthuse about dissonance and Miles Davis and Ravel and Can and John Cage and Ornette Coleman and fail to mention a single other “pop” artist at any stage of our discussion. Surprisingly, he doesn’t see the unorthodox trajectory of his career as anything other than logical, even inevitable. Surely, you’ll suggest, as the first hit singles were spilling from Talk Talk’s strangled debut album, The Party’s Over, he would never have seen himself ending up here? But no. “The thing is, those records were just driven by wanting to not to repeat ourselves,” he almost whispers. “To me, it doesn’t look odd.”

After that maiden album, things improved rapidly for Talk Talk, partly through the addition of producer/collaborator Tim Friese-Greene. Their second offering, It’s My Life, was still in the synth-pop mould, but hits like the title track and Such a Shame were imbued with a shimmering depth and subtlety their labelmates Duran Duran would never get anywhere near. By The Colour of Spring (1986), the group had shrugged off the earlier perceptions of them, ditching synths, trading their catchy but clever four-minute pop songs for more expansive, intricate ones. The best-known tune from that period, Life’s What You Make It, was predicated on a four-note piano bassline that stayed constant from start to finish, allowing Hollis’s voice and the other instruments to swirl around it - especially guest musician Steve Winwood’s swelling organ and the monumental guitar hook contributed by Pretenders guitarist Robbie MacIntosh. Not only was this a rousing number, it was devilishly clever. Talk Talk were now big stars on both sides of the Atlantic.

It is easy to see how EMI’s accountants might have been a tad peeved when they heard The Spirit of Eden two years later, inspired though it was. Hollis and Friese-Greene had reached the end of what they could do within a standard pop format. They had decided to move beyond it.

“The Spirit of Eden was definitely the album where I thought, ‘This is it. This is what we’ve been reaching for,’ “ Hollis now says. “Two things came together. First, because we’d previously sold so many records, we had a very large recording budget, which we decided to use to give us freedom to experiment. And second, digital recording had just come in.”

Most artists were fired by the clarity of the sound that could be produced in digital studios, but Talk Talk saw further ways of harnessing the new technology. Now music could be recorded, then moved around - cut and paste if you like - without the degeneration in quality that would occur with traditional tape recording systems. The Spirit of Eden was the first album to test the limits of this development. The idea was to improvise, as a jazz band would, then take the elements and arrange them into an album structure afterwards. Thus, the playing was fluid and exploratory (“A musical idea will never be as good as the first time it’s expressed,” Hollis notes), while at the same time being subjugated to the requirements of the piece as a whole. The mood was sombre, reflective, but with an elegiac afterglow that drew you back again and again. And still does.

Talk Talk made one more fine album, Laughing Stock, in 1991, before going their separate ways. “There was no big split,” Hollis shrugs. “By the end, everything was so loose that walking away didn’t seem like a wrench. We’d reached an end point.” In execution, Mark Hollis, the album, turns The Spirit of Eden on its head. In the intervening years, its maker had learnt to read and write music and had been composing short pieces for woodwind and piano (“just for the sake of it, not with any notion that it would be heard by anybody else”). He put his new skills to good use: the delicate tendrils of woodwind and brass that lead into the bluesy track A Life (1895-1915) or the spare, brilliantly evocative piano figures that underpin Inside Looking Out and the opening spiritual, The Colour of Spring, would probably have been beyond him previously.

“The idea was to have carefully worked-out structures, within which the musicians would have a lot of freedom. I’d just say to them, okay, we’re here , we want to get there - now let’s play. And I wanted there to be no more than four or five things happening at any one time. Over the course of the record, there are probably 20 musicians involved, but I wanted it to feel like a small combo from start to finish.”

This combines with the fact that everything has been recorded acoustically - almost unheard of nowadays - to create a rare, passionate, intimacy, a stillness of a type that many pop-inclined listeners may never have experienced before. “It’s nice to take your hearing down a step,” Hollis remarked recently. “There are ways of listening rather than just hearing, if you’re prepared to make the effort.” On the evidence he presents, few would deny that it’s an effort worth making.

^ go back to topThe Times: 30th January 1998

The former mainstay of Talk Talk, singer and guitarist Mark Hollis moves in a leisurely way his wonders to perform. Seven years since the last Talk Talk album he emerges with the first offering under his own name, a collection of quiet, still and scrupulously sculpted pieces played entirely on unamplified acoustic instruments: piano, guitar, a wind quintet, harmonica, harmonium, double-bass, percussion and occasional drums.

With his distinctively high, pleading tone, and a style of enunciation so approximate that it makes Van Morrison sound like Vera Lynn, Hollis sings with a heartbreaking purity of emotion, while the music unfolds like ripples spreading on the surface of a pond. The result is frequently mesmerising.

^ go back to topDer Spiegel: 26th January 1998

REDUZIERT: Die Wandlungen des Mark Hollis finden viele seiner Fans äußerst merkwürdig: In den achtziger Jahren hatte er mal eine Band, die Talk Talk hieß; ihr größter Hit war "Such A Shame". Weil Hollis trotzdem nicht zufrieden war, veränderte er Talk Talk ständig. Genauer gesagt: Er reduzierte radikal. Erst die Songs, dann die Band. Deshalb ist sein erstes Soloalbum auch ein Meisterwerk der Stille geworden. Leise, fast behutsam erklingen da Bläser oder ein Klavier, und immer wenn seine Stimme zu hören ist, möchte man die Luft anhalten, um sie nicht zu vertreiben. Daran sollte er vorerst nichts ändern

^ go back to topGaffa: 26th January 1998

Syv år er der gået siden det sidste livstegn fra Mark Hollis, hvor hans band Talk Talk udgav værket Laughing Stock. Et album, der ligesom forgængeren, et af firsernes absolut bedste albums Spirit of Eden, var kendetegnet ved sin blanding af pompøs og orkestral opsætning, hvor skingre udladninger blev afbrudt af pauserne mellem taktslagene - sekvenser, der befandt sig på grænsen til det selvudslettende. Albummet satte nye standarder, for hvordan morderne rockmusik kunne komponeres. Samtidig var det den største ko-vending i engelsk rock nogensinde, et kommercielt selvmord af de helt store.

Fra at have spillet hitorienteret synthrock på de første to albums skiftede bandet spor musikalsk, så eftertrykkeligt, at pladeselskabet opsagde kontrakten. Men for Mark Hollis var ambitionerne større end bare at befinde sig på hitlisterne og se kasseapparaterne snurre. Efter at have brugt år på at studere nodeopsætning og komponere musik for træblæseinstrumeter, skal forventningerne nu skal indfries med hans første soloudspil Mark Hollis. Og det bliver de, albummet ligger i umiddelbar forlængelse af Talk Talks to sidste udgivelser, men adskiller sig ved at være komplet akustisk, helt indtil sidste tone klinger ud. Væk er de pludselige dissonante udbrud, hvor guitaristen Tim Friese-Greenes guitar gennemhullede pauserne i det yderst komplekse lydbillede.

Mark Hollis er indspillet med Phil Ramekin (piano), Dominic Miller og Warne Livesey (guitar) og produceret af Hollis selv. Åbneren The Colour Of Spring er såre smuk kun med et regnvejrsdryppende piano, hvor hver tone for lov til at klinge helt ud, inden Hollis' skrøbelige stemme sagte sætter ind med en fornemmelse af, hvordan han smager på hvert eneste ord. The Watershed kunne ligeså godt være Talk Talk med det piskesmældsagtige percussion i forgrunden og en skinger blæser, der bevæger sig tæt på smertegrænsen. På The Gift og The Daily Planet nærmer opbygningen sig musikalsk en moderne form for jazz, hvor skæve vinkler og strittende forløb slår om sig i bedste Miles Davis-stil.

Det bemærkelsesværdige ved de fleste numre er stilheden mellem tonerne, hvor resonansen får lov til at klinge helt ud. Mark Hollis er hverken hit eller pop, men snarere moderne kompositionsmusik med klassisk tilgang, hvor eneren Mark Hollis endnu engang viser sin enorme musikalske begavelse og sjælelige instinkt på grænsen til genistregen.

5 stjerner *****

^ go back to topFinancial Times: 30th January 1998

It is always something of a risk to leave the comforting surrounds of a successful pop band and decide to go it alone. The post-Beatle careers of John Lennon and Paul McCartney are only the most famous, indeed near- mythical, examples of what happens when group chemistry is tampered with. For every Sting or George Michael who has successfully shed his early group persona, there are many more who have foundered in the attempt to go solo.

Take the sharply contrasting fortunes of two new solo debutants: on the positive side, there is Mark Hollis, former front-man of Talk Talk who, on his eponymous Polydor album, has produced an unexpectedly delicate, introspective work.

From the first silent moments of the opening ‘The Colour of Spring’ which has you checking the volume control, Hollis establishes a fragile, haunting mood which is sustained throughout. His voice is not the easiest to get on with, frequently striving for diminuendos for which he is technically not well-enough equipped, but there is plenty of expressiveness. He is aided by the album’s sparse acoustic accompaniments which make intelligent use of rare (in pop) instruments: a bassoon next to a harmonica, cor anglais, woodwind ensembles; all add to the sense of dislocation.

The work’s centrepiece is ‘A Life (1895-1915)’, inspired by Hollis’s reading of Vera Brittain, a plaintive lament which flirts with dissonance but never slips out of control. Here, the wide spaces in the music and wistful piano chords have us thinking of 1880s Impressionism rather than 1980s New Romanticism. A further couple of minutes of ambient silence at the end of the album intensifies the ghostly mood. Not one to play before a night out on the town.

You might, on the other hand, try Ian Brown’s Unfinished Monkey Business (Polydor) to liven things up a bit: the former Stone Roses man kicks off his solo debut with a crashing, home-made introduction of assorted noises-off which augurs well, particularly when followed by the cheerful cosmic bop of the new single ‘My Star’.

Sadly, the spirit of relaxed experimentation turns into cacophonous self-indulgence: things get bad with the inaptly-named ‘Sunshine’, which sounds like a rejected J.J. Cale demo, and worse still with the abysmal ‘Lions’ and its irritating refrain.

Where Hollis has used the detachment from his band to turn inward and explore terrain which is often neglected in pop music, Brown has thrashed around in several different directions, but made no progress. Even in such a notoriously unfettered art as pop, the first lesson of going solo is the need for discipline. Hollis has understood that; Brown has yet to get there.

Peter Aspden

^ go back to topMelody Maker: 31st January 1998

Book-ended by silence “Mark Hollis” is a quiet album on a silent place, recorded with just a couple of microphones strategically placed to pick up every nuance and texture of a few musicians gently stepping their way through Hollis’ painfully delicate songs.

Which is a million miles away from most people’s memories of Talk Talk, the studio-bound multi-layered creation responsible for some of the Eighties’ finest and most satisfying pop moments. It’s tempting to say that with this solo album, Hollis has stripped out the Eighties from his songwriting, and what we’re left with are the bare bones, the skeletal trees of melodies and songs, standing alone deep in uninhabited landscapes.

And there are the occasional echoes of Talk Talk here and there. Obviously, there’s them man’s voice. But where it was once fulsome and powerful, now it’s cracked and quiet. Words are swallowed and underplayed, like the tremulous woodwind which breathes across much of the album. There’s a hint at the fine, driving piano of the sublime 1986 hit, “Life’s What You Make It” - the song which for most people is Talk Talk - and the temptation to bellow: “Babe! Life’s what you make it” over the top is strong.

But the idea of “Mark Hollis” is just a stripped version of Talk Talk is hopelessly inaccurate. This is a whole new approach for him, the culmination of a couple of years’ worth of writing for a woodwind quintet and the gradual winding down of Talk Talk from the full-blown Eighties lush pop act to the increasingly personal and understated beauty of 1991’s “Laughing Stock”. While that record was somewhat undermined by EMI’s rehashing of old Talk Talk material and releasing a ghastly remix album, this one is emerging in a vacuum, naked and trembling.

Some of the arrangements might stir memories of animated Czechoslovakian folk tales and jar slightly to the ear tuned to the standard generic needs of the Nineties (guitars, drum machines, verses and choruses, please), but anyone who owns a Miles Davis album, has a soft spot for Led Zeppelin’s earlier acoustic dabblings and likes a change of pace from time to time will find a gem which will keep unravelling on every listen. Tracks like “The Daily Planet”, a brushed jazz cymbal-led tune of spine-tingling chords and some raw harmonica breaks, and “The Gift” - the first two bars of which will be sampled and turned into the template for a huge international rap hit before the millennium’s out - lodge into the memory while somehow remaining deliciously fleeting.

Oh sorry, did I come over all “Jazz Club” there? Well, erm, nice.

Mark Roland

^ go back to topMagic: Janvier 1998

Sept ans. Sept années sans doute passées tapi dans l’ombre, protégé contre toutes les révolutions technologiques, avançant à tâtons en tentant de résoudre ses équations musicales. C’est ainsi qu’on a imaginé à l’époque Mark Hollis, peaufinant le moindre changement d’accord, dirigeant à la baguette les seize musiciens chargés de l’accompagner dans l’accomplissement de son premier album solo. Entre notes d’une justesse rare et silences à la musicalité exacerbée, ce reclus iconoclaste avait pris le parti de se dévoiler, en janvier 1998, dans une nudité absolue, poursuivant le grand œuvre initié avec son groupe Talk Talk. Un groupe au parcours sidérant, débutant sous les auspices du néoromantisme et d’une vague electropop très prisée à l’époque de sa formation, en 1981. Signé sur la major EMI, le quatuor formé par Hollis (chant, guitare), Lee Harris (batterie), Paul Webb (basse) et Simon Brenner (claviers) obéit alors au diktat de son label, qui impose look, producteur et direction musicale afin de mieux profiter de l’air du temps, alors que le jeune leader prend son mal en patience. Le succès britannique est au rendez-vous à la sortie du très synthétique (1982), porté par les deux hits mineurs Talk Talk et Today. Mais pour Mark, demain est un autre jour. Déjà mutique, il commence sa mue à son rythme, sans vouloir effrayer ses employeurs et avec l’appui de sa section rythmique. Brenner débarqué, le néo-trio explore de nouveaux horizons.

Les compositions s’étirent, lorgnent vers l’acoustique et le groupe se trouve en la personne de Tim Friese-Greene son George Martin, son Martin Hannett, son Dave Fridmann. À l’aune de son deuxième LP, It’s My Life (1984), il se met certes à dos la Perfide Albion, mais trouve un chic public sur le Vieux Continent, conquis par la ritournelle mélancolique Such A Shame. Surtout, dissimulé derrière ses lunettes rondes et noires, Hollis prend confiance et conscience de ses possibilités. Il ouvre le pan de ses influences, parle musique concrète et classique, jazz et dub. Il élargit ses champs d’action, à l’image de l’ambitieux The Colour Of Spring (1986), laissant s’échapper malgré une certaine complexité un hit qui reconquiert le Royaume-Uni, puis franchit l’Atlantique, Life’s What You Make It. Une belle déclaration d’intention que Talk Talk semble prêt à appliquer à ses ambitions artistiques. Fort de ces succès populaires, le groupe pense pouvoir agir en toute impunité. Alors, sur Spirit Of Eden (1988), il tourne définitivement le dos à d’éventuelles velléités commerciales. Après avoir jeté le terme pop aux oubliettes, sa tête pensante, épaulée dans “l’écriture” par un Friese-Greene omniprésent, préfigure le “post-rock, The Verve et Radiohead”, comme l’écrit, en avril 2009, Alan McGee dans The Guardian. Cette musique improvisée, enregistrée dans l’obscurité puis agencée en studio par ces véritables sculpteurs sonores, déplait à ce point au label que ce dernier va jusqu’à traîner la formation et son leader devant les tribunaux pour avoir conçu un disque anticommercial.

Débouté, EMI va se venger en réalisant, en 1990, le best of Natural History, puis, l’année suivante, une compilation d’abominables remixes, History Revisited, commandités sans l’aval d’un Mark Hollis outré. Il claque d’ailleurs la porte de sa maison de disques, qu’il… attaque à son tour en justice, toujours en quête de sa liberté artistique absolue. Ce que lui promettent Polydor et la légendaire enseigne de jazz Verve, sur laquelle voit le jour Laughing Stock (1991), fort de six compositions au charme crépusculaire et aux tensions obsédantes, où se croisent les ombres de Miles Davis, La Monte Young ou Tim Buckley, entre inflexions free et accents folk. On ne le sait pas encore, mais ce cinquième chapitre plongé dans un clair-obscur rayonnant sera le chant du cygne de Talk Talk. Muets, certains de ses membres ne le restent pas bien longtemps puisque Harris renoue avec Paul Webb (futur metteur en son de l’échappée solitaire de Beth Gibbons, en 2002) et prend ses quartiers au sein de O’Rang, dont la musique abstraite se décline sur deux albums au charme onirique – Herb Of Instinct en 1994, puis Fields & Waves deux ans plus tard. Influence absolue de bon nombre d’ambassadeurs du post-rock (à commencer par Labradford et Bark Psychosis) et autres représentants d’une faction du trip hop (le premier LP d’Archive, entre autres), l’ombre de Talk Talk plane sur la fin du XXe siècle.

Hollis, lui, s’en moque, préférant donc peaufiner la suite logique de son épopée sonore. C’est pour lever le voile sur cette œuvre monochrome et faire la lumière sur ces années de silence que l’on était partis à Londres dans les frimas de l’hiver 1997-98, afin de rencontrer un homme que l’on pensait taiseux et timide, avant de découvrir un musicien accueillant et plus bavard que son art. Certes, au terme d’une interview réalisée dans un bureau de Polydor aussi dépouillé que les compositions de ce disque funambule, Mark Hollis s’était montré incapable d’évoquer son avenir musical. Quelques mois plus tard, sa présence au piano sur l’album épouvantail de UNKLE, Psyence Fiction (1998), laissait penser que l’homme avait de la suite dans les idées et des envies concrètes. Pourtant, douze ans plus tard, ce sont les paroles de A New Jerusalem qui résonnent ad libitum : “Heaven burn me/Should I swear to fight once more…”

Magic : Vous aviez disparu de la circulation depuis 1991, et la sortie de l’album de Talk Talk Laughing Stock…

Mark Hollis : Après un disque, il s’ensuit toujours pour moi une période pendant laquelle j’éprouve le besoin de faire le vide… Personnellement, au terme de l’enregistrement de Laughing Stock, j’étais arrivé à un stade où il fallait vraiment que je prenne du recul. De toute façon, je refuse de me sentir obligé de composer dans un cadre précis. Je ne supporte pas l’idée que des compositions doivent obligatoirement former un disque. Ce qui ne signifie pas pour autant que pendant ce temps, je ne fais plus de musique, bien au contraire… À une époque, j’ai surtout écrit des pièces instrumentales, certaines très simples mais d’autres plutôt fragmentées, que je destinais à des quatuors à cordes.

Et cette période a-t-elle influencé votre approche musicale pour ce disque ?

Oui, énormément. Pour Spirit Of Eden et Laughing Stock, nous avions imaginé des arrangements impliquant un nombre incalculable d’instruments. Cette fois-ci, au contraire, je voulais diminuer leur nombre. Je souhaitais revenir à une certaine simplicité tout en arrivant à suggérer les mêmes impressions, les mêmes émotions. Pour arriver à matérialiser ce qu’on a en tête, il faut savoir parfois prendre son temps… Effectivement, six années, ça peut paraître énorme. Mais pas pour moi. (Sourire.) Tu commences à composer parce que tu aimes la musique, un point c’est tout. Et cet amour doit rester la seule raison valable, il ne doit pas y en avoir d’autres. Mais il finit par arriver un moment où tu en as marre de trouver encore et toujours la même solution à un problème mélodique que tu as déjà résolu dans le passé… Tu te lasses à force de retomber toujours sur un même son, une même note, une même approche. C’est ce qui m’est arrivé. Et il a donc fallu que je trouve d’autres issues. (Sourire.)

L’un des aspects primordiaux semble être votre utilisation du… silence, parfois à l’intérieur même de la composition.

Tout à fait ! Mais il existait deux autres notions essentielles… La première était que l’album soit entièrement réalisé à l’aide d’instruments acoustiques. Ça peut paraître prétentieux, mais j’aime l’idée d’une musique pouvant exister hors d’un cadre temporel précis. Je souhaiterais que l’époque à laquelle j’enregistre ne soit pas “perceptible”. Et je crois que seule l’acoustique peut offrir une telle possibilité. En plus, elle te permet d’utiliser à merveille la résonance des notes, surtout lorsque tu joues à un niveau sonore assez faible. Je suis toujours impressionné par cette nature si fragile de la musique… Quant à la seconde notion, elle est liée avec les problèmes que j’évoquais tout à l’heure et cette obsession de ne pas les résoudre de la même manière. D’ailleurs, pour cela aussi, l’acoustique s’imposait… Car il était ainsi bien plus difficile de trouver des solutions. (Sourire.)

Dès lors, est-ce que votre travail sur le son ne prend pas le pas sur la chanson ?

C’est une question piège… (Il sourit et réfléchit.) Aujourd’hui, il est évident que ma façon de composer tient plus compte du son que de la chanson. Ceci dit, je suis convaincu que les compositions doivent tout de même épouser une certaine forme, accepter un cadre. Maintenant, pour moi, le terme même de chanson implique une structure bien trop définie. Je préfère laisser “voyager” mes morceaux et voir par instant s’ouvrir des portes qui permettent de continuer le voyage. Mais il ne faut pas tomber dans le travers inverse et se dire que dans ce cas, tu es libre de faire tout et n’importe quoi…

Après avoir enregistré pendant dix ans au sein d’un groupe, est-il facile de réaliser un disque sous son propre patronyme ?

En fait, si je sors cet album sous mon nom, ce n’est ni par volonté, ni par caprice… Mais en toute honnêteté, je ne pense pas que ce disque puisse être envisagé comme une œuvre de Talk Talk. Cela aurait été mentir que de l’avoir crédité au groupe. D’autant que l’une des pièces maîtresses en était Tim Friese-Greene. Et le simple fait qu’il ne soit pas impliqué dans ce projet m’interdisait l’utilisation de ce nom…

À quel moment, avez-vous su que vous n’alliez pas retravailler avec Tim Friese-Greene : dès que vos compositions ont pris forme ?

Oui, c’était alors une évidence. Mais déjà avant… À la fin de Laughing Stock, j’avais deviné que l’approche que nous avions adoptée était arrivée à son terme. Nous ne pouvions pas aller plus loin ensemble. Je ne voulais pas que notre esprit d’expérimentation se transforme en routine.

Le premier morceau porte le même titre qu’un album de Talk Talk, The Colour Of Spring…

La raison principale en est assez simple, en fait : je trouvais que ce titre illustrait parfaitement les paroles que j’avais écrites. Et puis, j’aime bien croiser les références. Je me suis déjà amusé à le faire… Le dernier single extrait de The Colour Of Spring s’intitulait I Don’t Believe In You et celui qui a suivi, le seul que l’on ait sorti de Spirit Of Eden portait comme titre I Believe In You. (Sourire.)

Sur votre disque, on trouve ce long morceau, A Life (1895-1915), dont le titre reste assez énigmatique…

Il évoque une personne qui meurt à l’âge de dix-neuf ans, une année après le début de la première guerre mondiale. Et dans ce cours laps de temps, elle a connu un changement de siècle, toute l’hystérie qui a régné avant la déclaration de cette guerre, la propagande puis la triste réalité… Je ne suis pas du tout un passionné d’Histoire mais j’étais très intéressé par cette période aussi ai-je lu beaucoup d’ouvrages la concernant.

Vous vous intéressez à la scène musicale actuelle ?

Sincèrement, ce n’est pas qu’elle ne m’intéresse pas, mais je n’ai pas le temps ! J’écoute énormément de musique mais surtout du jazz de la fin des années 50 ou du début des sixties, ainsi que de la musique classique des années 20 : ce sont les deux époques que je préfère… Et il me reste encore plein de choses à découvrir. Alors, je consacre tout mon temps libre à rattraper mes lacunes. Mais je ne cherche pas du tout à éviter la production moderne.

D’ailleurs, la production est très proche du jazz…

(Il sourit.) Quand tu te tournes vers le passé, tu t’aperçois qu’il existait une approche de la production complètement différente… Aujourd’hui, en particulier en Angleterre, on a l’impression que le terme “production” est devenu un gros mot. Dans les années 60, sur les disques de jazz en particulier, mais aussi dans le rock, le résultat était souvent l’œuvre d’un boulot en commun. Prends quelqu’un comme Jimmy Miller par exemple : il bossait toujours avec Glyn Johns et les deux étaient complémentaires. L’un était là pour prêter attention aux arrangements alors que l’autre était complètement obnubilé par le son. C’est pourquoi Phil Brown a joué un rôle essentiel dans la conception de mon disque… Ce travail mutuel est pour moi fondamental. Au jazz, j’ai aussi voulu emprunter cette sensation de live, même si tout le monde ne jouait pas en même temps, mais par petits groupes… En fait, nous n’utilisions que deux micros pour enregistrer.

Vous avez fait appel à beaucoup de musiciens ?

Seize personnes jouent sur le disque, des gens avec qui j’avais déjà travaillé, comme Robbie McIntosh, et des personnes qui m’ont été recommandées, comme Ian Dickson… Il fallait que je sois sûr que tout le monde puisse comprendre où je voulais en venir.

Vous leur avez-vous laissé une certaine liberté ?

Liberté ? (Il prend son temps.) Oui, en quelque sorte, dans le sens où je laisse à chaque musicien la possibilité d’opter pour plusieurs interprétations possibles. On enregistre souvent plusieurs versions… Plus rapides, plus lentes, plus mélancoliques. J’ai toujours considéré comme primordial le fait d’utiliser la personnalité d’un musicien, afin qu’il apporte sa touche, son interprétation ou plutôt sa vision au morceau. Mais il n’y a aucune forme d’improvisation sur le disque. Enfin si, deux : la trompette et l’harmonica The Watershed… Mais pour le reste, on s’en est tenu à ce qui était écrit.

Votre musique a une dimension très visuelle. Vous seriez attiré par l’exercice de la bande originale de film?

J’adorerais ça. J’aime énormément le cinéma, en particulier l’école européenne… Mes deux films favoris sont Les Enfants Du Paradis et Le Voleur De Bicyclettes. Dès lors, le problème se poserait pour moi de trouver un long métrage aussi fort. Sans oublier qu’il faudrait que quelqu’un ait envie de faire appel à mes services… (Sourire.) Il y a très longtemps, on m’avait demandé de composer un thème pour un documentaire. J’avais demandé toute latitude et j’avais prévenu que le résultat serait très différent de ce que je pouvais faire alors avec Talk Talk. Comme de bien entendu, on m’avait laissé carte blanche, mais une fois que les gens ont écouté le résultat, ils m’ont demandé si on ne pouvait pas rajouter un peu de batterie, faire quelque chose de plus enjoué… J’ai donc tout foutu à la poubelle !

Il vous arrive d’écouter vos anciens disques…

Non, jamais ! Dès que le mixage est terminé, je ne réécoute plus rien. Pendant l’enregistrement, tout est encore fluctuant, tu peux faire évoluer tel ou tel détail… Mais au mix, les morceaux prennent leur forme immuable : tu es arrivé à la fin de ton travail et dès lors, il faut savoir passer à autre chose pour essayer d’avancer.

Vous pensez qu’il vous faudra encore un septennat avant de finaliser un nouveau disque ?

C’est impossible à dire ! Il faut savoir que j’avais l’intime conviction de tenir mes derniers enregistrements en Spirit Of Eden, puis en Laughing Stock, alors… (Sourire.) Tout ce que je sais, c’est que je vais continuer à composer. Je veux utiliser le piano avec une approche très minimaliste. J’ai envie de jouer sur la résonance des notes, essayer de retrouver une certaine innocence. Mais aujourd’hui, personne ne peut savoir quelle sera la finalité de ces travaux. Même pas moi…

Christophe Basterra

^ go back to topMagic: January 1998

Magic: You had disappeared from circulation since 1991, and the release of the Talk Talk album Laughing Stock ...

Mark Hollis: After a record, there always follows for me a period where I feel the need to create a vacuum ... personally, after the recording of Laughing Stock, I had reached a stage where it was I ready take a step back. Anyway, I refuse to feel obliged to compose within a specific context. I can’t stand the idea that compositions are obliged to be made into a record. That does not mean that during this time, I didn’t make any music, far from it ... At one time, I mostly wrote instrumental pieces, some very simple but others rather fragmented, which I intended for string quartets.

And this time influenced your musical approach for this record?

Yes, very much. For Spirit Of Eden and Laughing Stock, we imagined arrangements involving countless instruments. This time, however, I wanted to reduce their number. I wanted to return to a certain simplicity while achieving the same impressions, the same emotions.

In order to materialize what I had in mind, it is necessary you know to sometimes take some time ... Indeed, six years, it can seem overwhelming. But not for me. (Smiles.) You start to compose because you love music, and that’s all. And this love must remain the only valid reason, there should not be others. But eventually there comes a time when you’re tired, again and again trying to find the same solution to a melody problem that you have already solved in the past ... You’re weary through always falling down on the same sound, the same note, the same approach. This is what happened to me. And therefore I had to find other outlets. (Smiles.)

One primary aspect seems to be ... your use of silence, sometimes within the same composition.

Absolutely! But there were two other key concepts ... The first was that the album was created entirely with acoustic instruments. It may sound pretentious, but I like the idea of music that could exist outside of a specific time frame. I wish the time I record is not “visible”. And I believe that only acoustic instruments can offer such a possibility. In addition, it allows you to use the wonderfully resonant notes, especially when you play at a fairly low noise level. I am always impressed by this kind of so fragile music ... As for the second concept, it is linked with the problems I mentioned earlier and this obsession does not resolve the same way. Moreover, for this too, the sound was needed ... Because it was so much harder to find solutions. (Smile.)

Therefore, does your work on the sound not take precedence over the song?

This is a trick question ... (He smiles and thinks.) Today, it is clear that the way I compose mostly reflects the sound of the song. That said, I am convinced that the compositions still need to marry a certain form, accept a connection. Now, for me, the very term ‘song’ implies a too well defined structure. I prefer to let my pieces “travel” and see how they open doors that allow you to continue on a journey. But one should not fall into the opposite extreme and think that in this case, you’re free to do everything and anything ...

After recording for ten years in a group, it is easy to make a record under your own name?

In fact, if this album is released under my name, it’s not through choice or caprice. It’s because I honestly don’t think this record can be considered a Talk Talk work. It would have been dishonest to have credited it to the group. Especially as one of the centerpieces was Tim Friese-Greene. And the simple fact thatwas that he was not involved in this project, so I fobade the use of the name ...

At what point did you know that you were not going to work again with Tim Friese-Greene: As soon as your compositions took shape?

Yes, it was so obvious. But even before ... At the end of Laughing Stock, I guessed that the approach we had adopted was at an end. We could not go further together. I did not want our spirit of experimentation to become routine.