Court of Appeal: 23rd May 1989

In the Supreme Court of Judicature

Court of Appeal (Civil Division)

On Appeal from the High Court of Justice

Chancery Division

23 May 1989

Lord Justice O'connor Lord Justice Mustill and Lord Justice Nourse

Tuesday 23rd May 1989

Representation

MR STEPHEN C. DESCH, Q.C. , and MR RICHARD SLOWE , instructed by Messrs Gentle Jayes, appeared for the Appellants (Defendants).

MR ROBERT M. ENGLEHART, Q.C. , and MR DAVID PARSONS , instructed by Messrs Joynson Hicks, appeared for the Respondent (Plaintiff).

JUDGMENT (Revised)

LORD JUSTICE O'CONNOR:

I will ask Lord Justice Nourse to give the first judgment.

LORD JUSTICE NOURSE:

This is an appeal against a decision of Mr Justice Morritt on the construction of an exclusive recording agreement. Shortly stated, the question is whether a notice given by the record company to extend the agreement for a further period was or was not given in due time.

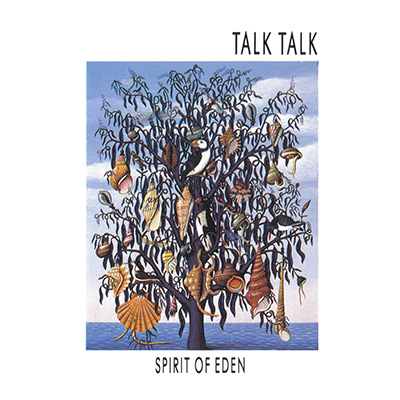

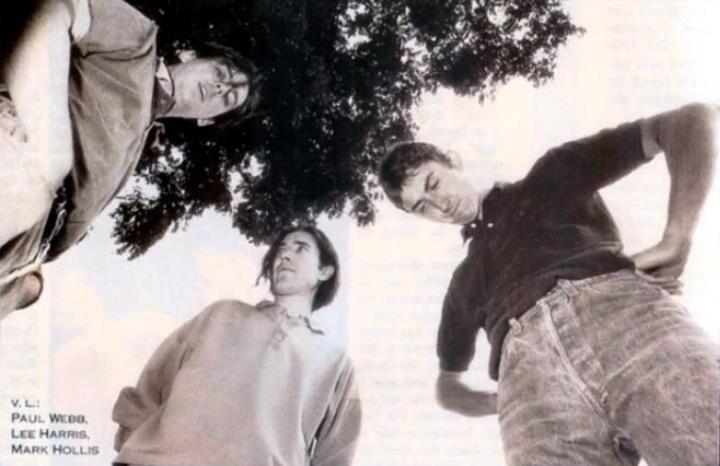

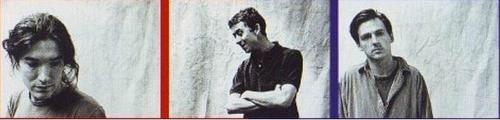

The agreement, which was dated 26th November 1981, was made between the plaintiff, EMI Records Limited (called “the Company” ) of the one part and the defendants, Mark David Hollis, Lee David Harris and Paul Douglas Webb and a fourth individual, who were the members of the pop group known as “Talk Talk” (called “the Artists” ) of the other part. Its material terms are in part contained in the definitions of expressions used in the agreement, and to some extent they arise by necessary implication. At the risk of some imprecision I will attempt to describe the general nature of the agreement in a summary manner.

The agreement was to last for an initial period of one year,. together with up to four further one year periods at the option of the Company, each such option to be exercised during the preceding period and so that any period might in certain circumstances be extended at the discretion of the Company or in any event with the agreement of both sides. During each period, including the initial period, the Artists were to record one obligatory album. During the option periods the Company was entitled on three separate occasions to require the Artists to record up to three further albums, called Overcall Albums, but not more than one during any one option period. The obligatory and Overcall Albums were together referred to as “the minimum commitment” . I shall have to refer to part of that definition later. At this stage I need only refer to the definition of “album” in clause 1 of the agreement: “shall mean a double-sided 12” disc Record which is designed to be played at 33? rpm and which is commercially suitable for release to the public.”

By clause 2(B) it is provided as follows: “THE ARTISTS will during the Agreement Period attend at such places and times reasonably convenient to both the Artists and the Company as the Company shall reasonably require and shall render such Performances as the Company and the Artists shall mutually approve for reproduction on Record” . There then follow four provisos, of which I must read the first two: “(i) in deciding what Performances to select for reproduction as aforesaid the Company shall have regard to any wishes expressed to the Company by the Artists as well as such other circumstances as are relevant. (ii) the minimum number of Performances which the Artists shall render for the Company as aforesaid and which the Company shall record shall be not less than the Minimum Commitment.”

The Company's several options to extend or further extend the agreement are contained in clause 3. That which is relevant for present purposes is The Third Option, which is contained in sub-clause (C), being expressed so far as material in these terms: “THE COMPANY shall be entitled (if it has exercised the Second Option) to extend this Agreement for a period of one (1) year ( ‘the Third Option Period’ as extended as herein provided) on giving notice in writing to the Artists before the expiration of the Second Option Period (or as the case may be on the Expiration of the Extension Period (as herein defined) of the Second Option Period in which event the Company shall have thirty days from the end of such Extension Period to extend this Agreement for the said period of one year) and all the provisions herein contained (except this sub-Clause) shall apply in respect of the Third Option Period or as the case may be the aforementioned Extension Period.

Clause 4 is headed “Recording Sessions” . The first two of its three sub-clauses are in these terms: “(A) THE ARTISTS shall at the reasonable request of the Company repeat any Performance for the purpose of producing a satisfactory Record commercially suitable for release to the public. (B.) AS the Company is paying the recording costs for recording Performances hereunder it shall accordingly be entitled to require the Artists to devote all the Artists' time and attention during recording sessions to producing satisfactory Performances hereunder.”

Throughout the agreement there are references to recordings being “satisfactorily completed” or to the “satisfactory completion” of recordings. There are four such references in paragraph (f) of the definition in clause 1 of Minimum Commitment, being that part of the definition which deals with the Overcall Albums and to which I will return later. Furthermore, by sub-clause (B) of clause 7, which is headed “Use And Performance” , the Company agrees “to release such Performances on Record in the United Kingdom prior to EITHER the expiry of 4 (four) months from the date of satisfactory completion of the recording of such Performances…” .

Finally, in paragraphs (iv), (vi), (vii), (ix) and (x) of sub-clause (I) of clause 10, which is headed “Royalty Provisions” , there are provisions for the payment by the Company to the Artists of advances of specified sums within fourteen days of “the satisfactory completion of the recording of” each of the various albums.

No difficulty appears to have arisen during the early years. On 25th October 1982 the first option was exercised during the initial period and by a letter agreement dated 27th September 1983, which also dealt with a number of other matters, the first option period was extended until 24th May 1984. On 18th May 1984, shortly before the end of that extended period, the second option was exercised. By that time the two obligatory albums for the initial and first option periods called “The Party's Over” and “It's My Life” had been released. At that stage no Overcall Album had been required.

On 15th May 1985, three days before the second option period would in normal course have expired, the Company required the Artists to make the first Overcall Album. It is agreed that the effect of that was to bring into play the final part of paragraph (f) of the definition of “Minimum Commitment” which is in these terms: “… such applicable Period of the Agreement Period shall be extended until the expiry of 3 (three) months from the date of satisfactory completion of the recording of the First Overcall Album…” The applicable period of the agreement for that purpose was the second option period. Accordingly, the effect of the requirement to make the first Overcall Album was to extend the second option period until the expiry of three months from the date of satisfactory completion of its recording.

So far there is no dispute between the parties as to the material events or the effect which they had. The dispute arises out of the terms of a further letter agreement dated 13th December 1985, by which date the first Overcall Album had not been produced, so that the second option period was still running. That letter was written by the Company and addressed to the three defendants who duly countersigned a copy of it. I will read the opening part of the letter in full:

“With reference to the Agreement between you and us dated 26th November 1981 as amended (hereinafter referred to as ‘the said Agreement’ ) in respect of Performances by you under your professional name ‘TALK TALK’ and with particular reference to a letter dated 27th September 1983 amending the said Agreement (such letter being hereinafter called ‘the said letter’ ) and notwithstanding anything to the contrary contained in the said Agreement and the said Letter it is hereby agreed as follows:-

“1. The Second Option Period of the Agreement Period is hereby extended until 31st December 1987 or until 3 (three) months after the completion of recording to our reasonable satisfaction of the First Overcall Album, whichever is the later date.”

In order that the dispute may be fully understood, some rehearsal of the largely undisputed facts is necessary. By 31st December 1987, more than two years later, the obligatory album for the second option period called “The Colour of Spring” had been released, but the recording of the first Overcall Album had not been completed. The story can then be taken up from the summary given by the learned judge, which I think is full and accurate-enough for present purposes. I. read at page 4 A-B of the transcript:

“What happened, as is shown by the uncontested evidence, is that towards the end of February 1988 but certainly after 24th February, the group delivered to EMI a cassette of the first overcall album. This was sufficient for EMI to assess its commercial viability, but further tests might have been required on the masters if they had to satisfy themselves as to its technical worth.

“Between 1st and 4th March 1988 Mr. Gatfield on behalf of EMI listened to the cassette. He had reservations as to its commercial suitability, and was not inclined to say that he found it to be suitable. Mr. Aspin, the manager of the defendants, was told of this reservation, and it appears that Mr. Aspin himself had doubts. Accordingly, a meeting was fixed up to discuss the matter, and on 15th March 1988 that meeting took place with Mr. Gatfield and Mr. Wadsworth representing EMI and the first defendant and Mr. Aspin representing the defendants. At that meeting the defendants were asked if they would be prepared to re-record one track, and the first defendant indicated that they would not. Mr. Gatfield suggested either then or on some subsequent occasion that there might be substitution of some material, but this was not accepted by the defendants either.

“On 25th March 1988 the masters were delivered to EMI. Mr. Gatfield at that stage felt that he had no option but to accept and, as from that date, it is accepted that EMI was satisfied as to the recording of the first overcall album.”

From this it is clear that the cassette of the first Overcall Album had been delivered to the Company before 1st March 1988 and that the recording of the album had been completed by that date. However, it is also clear that it was not until 25th March that the Company was satisfied as to. the recording of the album. The crucial importance of these dates becomes apparent when I state the final material fact, which is that on 14th June 1988, within three months after 25th March but not within three months after 1st March, the Company gave a notice exercising the third option under clause 3(C) of the agreement. No point is taken on the notice as such, but the defendants say that it was given too late.

The question essentially depends on when, under the terms of the letter of 13th December 1985, the three month period started to run. The Company contends that it did not start until it was satisfied as to the recording. The defendants, while accepting that the Company had later to be satisfied, contend that it started when the recording of the album was in fact completed.

Mr Justice Morritt preferred the contention of the Company. On the grammar of the letter, against the background of the agreement, he had no hesitation in coming to the conclusion that the period began at the date on which the Company was satisfied as to the recording.

The matter had come before the learned judge on motion on 2nd November 1988 when the parties very sensibly agreed that the motion should be treated as the trial of the action. The list was too full for the case to be dealt with that day and it came on for argument as the first effective motion on the following day, judgment being delivered at the close of the argument. Although the judge's judgment shows an impressive grasp of this very complicated agreement, it is evident that we in this court, having been able to read the papers beforehand and with the benefit of arguments which have lasted for more than a day, are in a position to consider the matter more fully than would normally be possible in the conditions of a busy motions court. Indeed, if the case had been given the time estimate of three to four – hours which it was given in this court, it would, I think, have had to be stood over to come on as a motion by order.

By his order made on 3rd November 1988 the judge declared that the Company had validly exercised its option under the agreement in respect of the third option period and that the agreement remained in full force and effect. Against that decision the defendants appeal to this court.

Immediately before the letter agreement of 13th December 1985 the position was that the second option period had been extended until the expiry of three months from the date of “satisfactory completion of the recording of the first Overcall Album” . The first question is what is meant by that phrase. The primary submission of Mr Englehart, for the Company, is that it means completion of the recording to such a standard as to be satisfactory to the Company. I do not think that that can be correct. There is nothing in the single word “satisfactory” to show that it is the satisfaction of the Company alone which must be met. It could just as well be the satisfaction of the Artists as well as the Company, and indeed of anyone else who was competent to judge the merits of the recording. If “satisfactory” stood alone it would not, in my view, point to the satisfaction of any particular party or parties and would mean no more than “adequate” , which is indeed one of its dictionary meanings.

As it happens, it does not stand alone. By clause 4(A) of the agreement the Artists are obliged, at the reasonable request of the Company, to repeat any performance for the purpose of producing “a satisfactory Record commercially suitable for release to the public.” Those latter words echo the second requirement of the definition of “album” . The combined effect of that definition, the definition of “Minimum Commitment” , and clause 2(B) proviso (ii) is that the Artists are obliged to render sufficient performances to make obligatory and overcall records which are commercially suitable for release to the public. Clause 4(A), in the case of a repeat, equates a “satisfactory” record with one which is commercially suitable for release to the public. If that is expressly so in the case of a repeat, it must just as much be impliedly so in the case of an initial performance.

Although it is by no means an ideal state of affairs that some of the Artists' primary obligations under the agreement should have to be extracted in part from definitions and in part by implication, I have come to a clear view that on the construction of the agreement as a whole the expression “satisfactory completion of the recording” means completion to such a standard as will produce a record commercially suitable for release to the public. Whatever might have been said about “satisfactory completion” had it stood alone, the test of commercial suitability for release to. the public is one which is objective in the fullest sense – that is to say objective not only in standard but also in not being referable to the views of any particular party or parties. There can be no doubt that on that footing the satisfactory completion of the recording occurred on or before 28th February 1988 and that the three month period started on that date.

I should add that Mr Justice Morritt did not refer either to the definition of “album” or to clause 4(A). Although we have been told that those provisions were referred to in argument and that some reliance was placed on clause 4(A) on the defendants' side, it is I think clear that the significance which they have assumed in this court was not urged upon the learned judge.

Such being the position under the main agreement, what was the effect of the letter agreement of 13th December 1985 which, so far as material, was expressed to extend the second option period until “3 (three) months after the completion of recording to our reasonable satisfaction of the First Overcall Album” ? His primary submission having been rejected, Mr Englehart now submits that the effect of the letter agreement was to alter the pre-existing position and to make the actual satisfaction of the Company a pre-requisite for the running of the three month period,so that it did not start until the Company was satisfied on 25th March 1988. He emphasises that the Artists were protected by the necessity for the satisfaction to be reasonable, thus retaining the objectivity of the standard.

Although we have heard much argument on the point, it is really one of impression. For my part, while I can accept that the different wording expressed the Company's understanding of the effect of the main agreement (it had already been expressed in much the same terms in an earlier amendment agreement of 23rd March 1982 to which Lord Justice Mustill drew attention in argument), I cannot accept that it was the mutual intention, of the parties to alter the effect of the main agreement whatever it might be. As Mr Desch, for the defendants, has said, it was perfectly natural for the letter to concentrate on the concept of satisfactory completion in a manner which was unnecessary in the agreement.itself. But it is quite another thing to say that the parties intended to alter the pre-existing position in an important respect, as it were by a side wind and without spelling out their intention with greater clarity.

That is really enough to dispose of this appeal in favour of the defendants, but two further points must be mentioned. First, the question which took up the greatest part of the general argument both here and, I think, below was whether the completion of the recording or the satisfaction of the Company was the more suitable point of time for the three month period to begin. The Company contends that it would not necessarily know when a particular recording had been completed. The defendants contend that they would not necessarily know when the Company was satisfied with it and, moreover, that the Company could delay its being satisfied almost indefinitely.

I do not propose to go into the various arguments and counter arguments on this and the other related points which were discussed. Viewing the matter in the round, I think that on the terms of the agreement as a whole the defendants' contention is to be preferred. Clause 2(B) gives the Company, first, the sole right reasonably to require the Artists to attend at reasonably convenient places and times in order to render the necessary performances, and, secondly, an equal right with the Artists to approve the nature and content of such performances. In practice therefore the contractual position was that the Company had a large say in the nature and content of the performances and could control where and when they took place. Reliance to the same effect can also be placed on the terms of clause 4(B). In practice therefore the Company could, if it wanted to, operate a system whereby it would in practice know when a particular recording was complete.

It is perfectly true that in the present case the Company was content to allow the defendants to do everything on their own. But that cannot affect the true construction of the agreement. Moreover, I think that there is much to be said for the view that, in a case where the Artists are left to do everything on their own, the recording is not in fact completed until the cassette has been delivered to the Company. Before that event has occurred everything remains under the control of the Artists and some further variation can, if they wish, still be made. It is the delivery of the cassette which signifies the completion of their part in the proceedings, namely the recording.

Secondly, in support of the defendants' appeal to this court, Mr Desch has relied on an authority which was not cited below. That is the unreported decision of another division of this court (Sir John Donaldson M.R., Lord Justice Nicholls and Mr Justice Caulfield) given on 9th December 1987 in The Queen -v- Westminster City Council, Ex parte Hazan . That was a case whose outcome depended on the true construction of the definition of “certified date” for the purposes of the repairs grants provisions of the Housing Act. At the material time the definition was contained in the now repealed section 75(6) of the Housing Act 1974 , but there is a definition to the same effect in section 499 of the Housing Act 1985 .

Section 75(6) of the 1974 Act was in these terms:

“In this Part of this Act ‘the certified date’ , in relation to a dwelling in respect of which an application for a grant has been approved, means the date certified by the local authority by whom the application was approved as the date on which the dwelling first becomes fit for occupation after the completion of the relevant works to the. satisfaction of the local authority.”

It will be observed that the words “after the completion of the relevant works to the satisfaction of the local authority” are for practical purposes identical to the words in the letter agreement of 13th December 1985. Even with that wording it was held that the relevant event was the completion of the works and not the later satisfaction of the local authority.

Mr Englehart has submitted, correctly, that that case was decided not on a commercial contract but on a statute – moreover on a statute dealing with an entirely different subject-matter. He has elaborated that submission with a number of grounds of distinction in which I see great force. However, taking the view, as I have, that the letter agreement did not alter the position under the main agreement, it is unnecessary to express a view as to what effect the decision in Ex parte Hazan would have had in this case had the actual wording of the letter agreement been decisive.

I would allow this appeal.

LORD JUSTICE MUSTILL:

I agree.

LORD JUSTICE O'CONNOR:

I also agree.

MR DESCH: My Lords, then I ask for an order that the appeal be allowed, and may I ask your Lordships to order that the plaintiffs pay the defendants' costs here and below?

LORD JUSTICE O'CONNOR: You cannot resist that?

MR ENGLEHART: Clearly that must follow, my Lord. I do have an application to ask your Lordships for leave to appeal.

LORD JUSTICE O'CONNOR: No. You must go to their Lordships, Mr Englehart.

LORD JUSTICE NOURSE:

Mr Desch, having allowed the appeal, I think we dismiss the action, do we not?

MR DESCH: Yes.

LORD JUSTICE NOURSE: That is what is asked for in the notice of appeal.

MR DESCH: My Lord, yes.

LORD JUSTICE NOURSE: You do not want, as it were, a rival declaration to that which Mr Justice Morritt gave the Company?

MR DESCH: No, my Lord. Thank you very much.

LORD JUSTICE O'CONNOR:

So be it. The appeal will be allowed with costs; leave to appeal refused, and the result of that is that the action will stand dismissed with costs.

MR DESCH: I am obliged, my Lord. Costs here and below?

LORD JUSTICE O'CONNOR: Here and below, yes.

Order: Appeal allowed with costs here and below; leave to appeal to the House of Lords refused.